Tested Technology is dependent on its small team of advisers, contributors and backroom technicians. They do a good job. And letting them know this pays off. As any business management manual will tell you, keeping the team happy by giving credit where credit is due is an essential lubricant of a successful enterprise.

I take this a step further. You’re going to think me nuts but bear with me.

These days so much of what we do depends on technology. Technology that works smoothly, reliably, often invisibly. And keeps on working.

So I give the technology the praise and encouragement it deserves. Verbally.

Yes, I’ll pat my desktop computer as I go by and say: Well done. I open my laptop with a cheerful greeting: Thanks for yesterday*. I glance across the room at my NAS, give it a friendly wave, telling it: You’re indispensible.

Is this crazy? You might well think so but here’s the thing:

- Programmers do this with software all the time. They personify the program they’re writing and identify with it. “Let’s see, so the user inputs a value which I validate against this list and copy into this register. If it matches or exceeds the value in this other register I branch into… Ah, I see where we’re going wrong. But let’s do this instead. That’s brilliant—good job!”

- Hardware may not have a soul but you do. By making sure your equipment feels good about the job it’s doing you’re actually making sure that you feel good about the equipment.

These aren’t trivial points. Let’s take an example.

You have an urgent job to do this morning and your computer fails to boot. You check the battery and the BIOS but nothing gets it going. It’s failed you. You hate it.

Wrong attitude, obviously. Things aren’t good but if we carry on like this they’re guaranteed to get worse. Laptops have been hammered to death in cases like this.

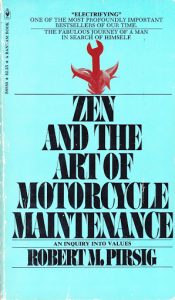

Robert Pirsig’s great book, Zen in the Art of Motorcycle Maintenence, is what we need here. In Chapter 24 he discusses “stuckness”, He defines this as “a mental stuckness that accompanies the physical stuckness of whatever it is you’re working on“.

Robert Pirsig’s great book, Zen in the Art of Motorcycle Maintenence, is what we need here. In Chapter 24 he discusses “stuckness”, He defines this as “a mental stuckness that accompanies the physical stuckness of whatever it is you’re working on“.

In this particular case, the machine his son Chris is riding needs fixing. And the fix is described in the motorcycle manual. Pirsig has great respect for the motorcycle manual and the science behind it and the motorcycle manual says that the fix first requires removal of the side cover assembly.

Which is fine, except that one of the screws holding the side cover assembly in place remains obstinately unremovable.

It’s stuck. But this isn’t the stuckness Pirsig wants to address. It’s the stuckness of mind following the discovery that the manual has nothing to say about this screw except that it needs to be removed.

Pirsig writes:

I think the basic fault that underlies the problem of stuckness is traditional rationality’s insistence upon “objectivity,” a doctrine that there is a divided reality of subject and object. For true science to take place these must be rigidly separate from each other. “You are the mechanic. There is the motorcycle. You are forever apart from one another. You do this to it. You do that to it. These will be the results.”

Overcoming this mental stuckness is, for Pirsig, a Zen-like process that requires the mechanic becoming as one with the stuck machine screw. This idea is derived from “Zen in the Art of Archery”, a once-famous best seller written in 1953 by the German philosopher Eugen Herrigel.

Herrigel’s book had a huge influence on Western thought in the ’50s, inspiring a welter of other “Zen in the Art of…” books, of which Pirig’s is the most highly regarded. Sadly, Herrigel’s account of his Japanese tuition in archery has since been shown to be largely fraudulent**—perhaps “mythical” would be a more diplomatic term.

It’s true that Pirsig isn’t able to tell us in detail how he addresses his and his son’s stuckness and how this does finally get Chris’s bike back on the road.

Thinking of the screw not as an abstraction, a class of item in the mechanics catalogue, but as an individual entity with a unique quality of being able to remain unmoving when other screws merely unscrew, opens up, says Pirsig, a horizon of possible solutions from WD-40, to drilling out the screw, or…

“…you just might, as a result of your meditative attention to the screw, come up with some new way of extracting it that has never been thought of before and that beats all the rest and is patentable and makes you a millionaire five years from now.”

But what the actual solution might have been is not his point and it’s not the point I’m making here.

But what the actual solution might have been is not his point and it’s not the point I’m making here.

It seems to me far better to have some faith in your IT equipment and even to develop a (yes, arguably one-sided) friendship with it than to be at odds with it.

Particularly when it’s not behaving as you expect.

Chris Bidmead: 1 Oct 2020