As regular readers will know, Tested Technology is a fan of projectors. And projectors, if you’ll pardon the seque, have fans. The fans are there to blow air to keep the system cool. But fans also suck in dust.

Air filters are standard features of 3LCD projectors like Epson’s and my original Hitachi PJ-TX200. Every hundred hours or so of use you need to remove the filter and vacuum out the dust it’s gathered. Typically, here in the UK, DLP projectors won’t be equipped with air filters.

This lead me to believe, for many years, that the optical path in a DLP projector is some kind of sealed unit, impermeable to external debris. I checked this point with Steve May of Home Cinema Choice and he was under the same impression.

But, no! I understand that this is true of a very few DLP projectors. Most of the projectors that have come the way of Tested Technology over the years, typically the budget end of the market, surprisingly excellent though they’ve mostly proved to be, are certainly vulnerable to accumulating dust in the light path.

I decided this was worth investigating further…

Dust revealed by the closing frames of “The Long Haul”, a marvellous 1957 British movie with a stunning performance by Diana Dors

WHEN WE REVIEWED THE Optoma UHD51 4K projector last year, it was set up in the office in place of our tried and trusted Viewsonic PJD7820HD, a crucial item of office equipment pre-dating Tested Technology.

The Viewsonic, our workhorse 1080p projector, has been with us for the past six years. We put it carefully back in its carrying case and filed it away in a corner for a month or so while we worked on (and had fun with) the Optoma.

When the Optoma review was done and the device returned to the manufacturer we reinstated the Viewsonic, reconciled to foregoing high dynamic range and returning to the normality of 1080p. What we didn’t expect to find was a picture that made the darker passages of any movie appear as if they were shot in a snowstorm (see picture).

Bright scenes were fine. But the projector proved entirely unable to implement fade-to-black in anything approaching the way the director intended. Blurry white and grey spots marred the image. Dust had invaded the light path.

The Dust Invasion

Like a computer, the internal components of a projector are kept cool with fans. And like a computer, these fans are prone to sucking in any dust in the surrounding air. If dust accumulates on the fan dedicated to cooling the computer’s main processor the fan becomes less efficient, the cooling process is impaired and, sensing the increased heat, the processor will begin to throttle and may even stop altogether.

The processors in a projector can suffer the same fate. But long before that happens, accumulated dust is much more likely to show up in the form of a deteriorating image. The array of lenses responsible for the focus and zoom is complicated to dismantle and clean and dust spots developing here will appear as whitish grey blotches on the screen. A layer of dust forming on the mirror or prism used to fold the light path may be easier to access, but the cleaning process here needs to be carried out with care to avoid damaging the reflecting or refracting surfaces.

Dust can get burnt into the lamp

Dust in the lamp housing can cause premature dimming. Projector lamps run very hot indeed and layers of dust can even get burnt onto the glass.

Dust can also affect the colour rendition, even if it doesn’t appear anywhere in the light path. The rotation of the colour wheel will typically be monitored by a photoelectric cell that reads the interruptions of a tiny light beam to determine which colour is being presented at any instant. Dust on the photoelectric cell can create timing errors that result in colour distortion or even a complete shutdown.

In the case of Tested Technology’s Viewsonic projector, the offending dust wasn’t in the lens array or in the colour wheel. Evidently dust that had collected relatively harmlessly over the years at the bottom of the case had swirled into life when we packed up the device and stowed it away, turning it on its side. Some of that dust had found its way to possibly the worst place it could be. It had got into the DLP sub-chassis.

Dealing with Dust

How do I know this? I’d like to tell you I’d downloaded the relevant service manuals. equipped myself with the necessary tools, opened the projector up in a clean room and got to work on it myself. I can’t tell you that, though—I couldn’t muster the chutzpah.

It was never a very expensive projector, past its sell-by date now and probably replaceable for less than £500. But we’d got very fond of it over the years and I didn’t trust myself not to mess it up if I started twiddling with its entrails.

But as luck would have it, I did know someone ready and willing to do a proper professional job on the Viewsonic. James Davis runs an outfit called Ninatec in Canary Wharf. which happens to be within easy reach of Tested Technology Towers. Ninatec specialises in fixing computer notebooks and projectors. The work keeps James busy, particularly as he charges what are probably the best rates in and around London.

James was happy to offer Tested Technology a special price on the deal in exchange for a mention here. He was just thinking in terms of a link to his site. But it struck me that “Dust and your DLP Projector” might make a useful subject for a Tested Technology Data Sheet, where we could dig into the problem a bit deeper.

James was kind enough to provide photos of the repair in progress and also gives us a heads-up on projector maintenance to pass on to readers.

“Most of my projector repairs are because of dust.”—James Davis of Ninatec

James says that problems related to the motherboard electronics are “extremely rare”. Projectors brought in to Ninatec for repair are nearly always failing due to a build-up of dust. In the case of our Viewsonic, the dust on the mirror surface of the DLP chip wasn’t the worst thing that could happen.

Alternatively known as a DMD (digital micromirror device), this remarkable invention was an early implementation of a new class of electronic devices Nathanson had introduced called MEMS (micro electro-mechanical systems) that combine conventional microelectronics with tiny physical devices.

In the DLP chip, the physical devices comprise an array of minute hinged aluminium mirrors. When a beam of light is directed at the mirror array each individual mirror can deflect that beam in a different direction, depending on its angle at that instant. The angle of each mirror is controlled electrostatically by the electronics of the chip.

In effect, then, each mirror represents an individual pixel of light. At its simplest an individual mirror can either reflect the incoming light at that point into an outgoing focussing lens or dump that section of the beam into a “bin” out of sight. The focussed image of the DLP mirror surface will either show on the screen a white pixel at that point or a black pixel. Extended across the whole mirror array this gives us a method of showing a screen picture comprised of black or white pixels wholly governed by the electronics of the chip.

But the responsive dynamic control the electronics has over the mechanical mirrors takes this principle a step further. By vibrating the mirrors at different rates the DLP chip can manage the brightness of each pixel, providing levels of grey. Given sufficient number of pixels we now have the means to turn any digital monochrome movie into moving pictures on our screen.

But the DLP story needn’t stop there. There are several ways this technology can produce colour (see box below).

When the projector cooling system gets clogged with dust, James reports, the DLP chip is likely to overheat. Yes, the chip will typically be thermally coupled to a very large, finned heatsink. But the catch is that the connection between the heatsink and the chip is conventionally a blob of specially heat-conductive thermal paste and overheating dries up this paste. Once the dried paste becomes useless at conducting heat away the individual mirrors can start to fail and the image loses pixels.

Removing dust isn’t just a matter of applying a vacuum cleaner to the vents or blowing through them with an air can. Even if you remove the casing to get closer contact with the components, by sucking or blowing air you may simply be moving harmless dust into a position where it obstructs the light path or does serious permanent damage.

“One of the worst things to do is to remove the top and try cleaning it with an air can”—James Davis of Ninatec

The DLP+lens assembly that needs to be set aside before expelling dust from the main chassis. But, as you can see, the assembly has collected a fair bit of dust of its own.

The best thing you can do with a projector to protect against dust is just to leave it alone. If a dust cleaning operation really becomes necessary, it’s essential to:

- bring the projector into a dust free environment

- carefully open up the case

- remove the lens array together with the DLP sub-chassis and put them well out of the way

This is to avoid disturbed dust being transferred into the light path. Only with the projector disassembled like this should you do any vacuuming or blowing.

The Official View

It’s worth adding here that the official advice from Viewsonic is never to open up the casing. For their DLP projectors sold in Europe the message is: “Degradation with components due to dust, is not a main factor and filters are not required to be changed.” For the Asian market, due to the environment “there are options to change the filter”.

The Viewsonic PJD7820HD was first launched in 2013.

I found the phrase “…filters are not required to be changed” a little odd. In my experience, there are no filters in any of the DLP projectors I’ve come across, and James confirms that “There are certainly none in any BenQ, Viewsonic, Acer or Optoma projectors that I have serviced.”

I’d also take issue with dust not being “a main factor”. From Tested Technology’s own findings (backed up by James’ repair experience) dust is very much the predominant cause of problems in DLP projectors as they get older.

Let’s try to unpick that. Viewsonic projectors have a very decent warranty period of three years (excluding the lamp, which is guaranteed for one year). In a typical European environment, I’d agree, dust problems are very unlikely to arise during that time. If this does happen, no doubt Viewsonic would honour the warranty. Beyond that period, for an entry-level DLP projector, a typical clean and repair (excluding Ninatec’s bargain rates) might well approach or exceed the cost of a new device.

This could be why Viewsonic (and presumably other comparable vendors*) either don’t see, or feel able to deny, the dust problem. Once it’s outlived its guarantee and/or first lamp change, manufacturers expect you to replace the whole thing.

That philosophy certainly keeps production rolling along. But it’s becoming increasingly unfashionable now we’re starting to think about taking care of the planet.

![]() has also weighed in with some official notes. The company’s UK senior sales manager, Lee Dent, makes a distinction between home theatre projectors, which aren’t going to be on for long periods of time and projectors designed for applications like education, where the devices may be in constant use.

has also weighed in with some official notes. The company’s UK senior sales manager, Lee Dent, makes a distinction between home theatre projectors, which aren’t going to be on for long periods of time and projectors designed for applications like education, where the devices may be in constant use.

For home theatre use, says Dent, “dust isn’t much of an issue” (which seems to be much the same story as Viewsonic’s). Projectors in BenQ’s home theatre range tend to carry a guarantee of two years, with one year or 2,000 hours for the lamp,

For heavier use, Dent recommends the range of BenQ projectors in the Dust Guard series.

These have an IP5X rating for protection against dust and fine particles, preventing dust damage and maintaining image quality for longer. The BenQ Website claims that Dust Guard offers:

-

- Uninterrupted learning in the dustiest environments

- Extend projector lifetime and reduce the frequency of projector maintenance by a third

- Ultra-high image quality without colour decay

The official, 3rd party-certified IP rating is significant. According to Dent: “Although some 3LCD projectors claim to be dust resistant, this isn’t IP rated, and therefore not as reliable”.

As with other manufacturers, Dent acknowledges that in some of the global markets dust can be more of an issue. Versions for these markets typically offer extra filtration,

to remove larger particles, preventing fans clogging.

As projectors find wider uses, in museums, for projector mapping or in immersive training, Dent sees dust prevention playing a larger part in projector manufacture. He regards a feature like BenQ’s Dust Guard becoming a standard—or perhaps essential—feature requirement in future DLP projectors.

This is the technique used in professional cinemas and for some very high end home theatre projectors. It’s expensive. Not just because you’re tripling the cost of the DLP chip—the three light paths have to be meticulously aligned in a much more rigid chassis. Mechanically and electronically, this arrangement is considerably more complex. Prices start at around £20,000

The commonest technology used in affordable single DLP projectors harks back to the pioneering days of television. The scanning disk was patented in 1885 by Paul Gottlieb Nipkow and became a fundamental component in the early television sets of the 1920s and 1930s.

Dust on a colour wheel can produce flickering, says James Davis. Once cleaned, “the colours look amazing”.

As a method of scanning a picture line by line for transmission, Nipkow’s disk had its shortcomings. Translated to the single DLP projector it has a much simpler role. Instead of a spiral of small, evenly spaced holes designed to deliver a whole frame pixel by pixel (very roughly speaking), the projector colour wheel, at its simplest, is segmented to deliver a rapid sequence of red, green and blue filtered light from the lamp onto the DLP chip. Electronics en route to the DLP chip will synchronously be splitting each frame into three colour separations in time with these filters.

The red, green and blue components of each single frame arrive on the screen so rapidly that the human eye blends the colours back to a close approximation of the original image.

The rotation of the wheel has to be tightly synced to the timing of the DLP’s presentation of the colour separated fields. As mentioned above, the speed of the wheel is typically monitored optically and therefore vulnerable to dust.

The arrival of the LED projector made it possible to dispense with the spinning colour wheel by replacing the hot white lamp with three banks of red, green and blue LEDs, flashing in sequence in time with the DLP. All the timings here are purely electronic, with the added bonus that the LEDs last very much longer than a hot lamp and run cooler, reducing the need for powerful fans. And therefore diminishing the dust problem. The downside of LED illumination is that it’s not yet able to attain the brightness of a hot lamp.

Final Thoughts

But during the decade (and more) that I’ve been pontificating to readers about digital projectors I had always assumed that dust could never be a problem for DLP technology.

That’s what I’ve been telling readers. And that’s where I’ve been completely wrong.

An unfiltered 3LCD projector is certainly going to experience dust problems long before a DLP projector (hence the strict filter regime). But Dust Death awaits budget DLP projectors too, in the longer term.

More expensive projectors (See BenQ above) are able to protect the projector’s light engine rather better against dust. But any sealing can’t guarantee to be airtight as it will still require some kind of vent hole to cope with air expansion.

For the general run of budget DLP projectors like the Viewsonic PJD7820HD I’d recommend that within the warranty period, during which the manufacturer would be expected to meet any repair costs, you should be able treat your projector with the same sort of care you’d afford your laptop. Set it up, use it, put it away, carry it about and so forth.

But when that warranty period runs out…

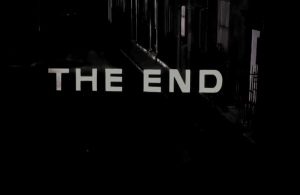

The same closing frames after the Ninatec treatment

Things are different now. Your DLP projector may have accumulated an internal layer of dust, currently resting innocuously at the bottom of the case. Leave it there. Don’t, whatever you do, let a vacuum cleaner or air blower anywhere near the thing. If you must pack it away, carry it carefully and keep it horizontal.

This may seem super-cautionary and perhaps it is. I’d love to be able to give more specific advice on the subject but several of the DLP manufacturers I’ve approached about this haven’t seemed too willing to discuss the issue. So that’s how Tested Technology intends to treat its DLP projectors from now on.

If manufacturers do get back to me with contrary or supplementary advice, I’ll report back here.

Meanwhile, if your out-of-warranty projector should run into DLP dust problems, it looks as if an independent repairer like James of Ninatec might be your best bet.

Chris Bidmead: 2020/02/20

Thanks for the article, unfortunately for our little Viewsonic dust got shaken up all over the DMD, mirrors and lenses from repeated house moves. Having it mounted upside down from the ceiling only exacerbated the issue! Oh well, it has had a good life and thousands of hours of enjoyment… I’ve since taken it apart to get to the dust, but its innards aren’t published online and nothing will separate at a certain point. Plugged back in and living with diminished fade to black until the next one :)

Very sorry to hear that, RCW. The good news is that projectors seem to have got a good deal cheaper. If you manage to find one at a decent price that also has a sealed light path, do please let Tested Technology know.

—

Chris