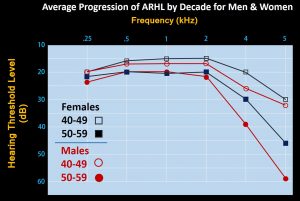

My credentials as a full-on audiophile, such as they might have been, were comprehensively blown at the beginning of this year. My audiologist revealed that my hearing starts to fall off at 1kHz and is technically classed as “severe” above around 8kHz. (The full story is here.)

The range of human hearing is generally reckoned to be between 20Hz and 20kHz, spanning some seven octaves. Some audiophiles claim that even sounds above 20 kilohertz need to be recorded and reproduced, as their presence will have some kind of effect on the notes within our audible range.

This has opened up a new market for “hi-res” audio material and the equipment to play it on. Equipment like iFi’s new nano iDSDBlack Label DAC. If you want to explore the field of hi-res, this device is an excellent start (full disclosure: ours fell into our hands at the London launch towards the end of last year).

You get a solid build and clean internals with an ambitious specification for a very decent price. Even if some of the upper reaches of those specifications may be falling on deaf ears.

IFI IS A SUBSIDIARY of the high-end (read “expensive”) audio vendor, Abbingdon Music Research. iFi focusses on the more affordable end of the hi-fi spectrum while drawing on the expertise and technologies of the mother-ship.

IFI IS A SUBSIDIARY of the high-end (read “expensive”) audio vendor, Abbingdon Music Research. iFi focusses on the more affordable end of the hi-fi spectrum while drawing on the expertise and technologies of the mother-ship.

The iFi nano iDSD Black Label DAC is a device that packs most of its capabilities into its title. It’s a DAC (digital to analogue converter) that is capable of decoding DSD (Direct Stream Digital) and is pocket-sized (nano)—not much larger, in fact, than a box of kitchen matches. DSD decoding isn’t its only talent: it handles many other digital formats, including FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec) and the ubiquitous but now deprecated (by audiophiles) MP3.

Well, hold that thought for a moment. The iFi nano iDSD Black Label DAC (no, I really can’t go on spelling that out in full—let’s just call it the Nano iFi, or the Niffy) doesn’t list MP3 among its capabilities. Snobbery? It’ll certainly play MP3s. Won’t it?

Actually, no. Present the Niffy with an MP3 stream direct from your computer or phone and you may get an output but it won’t be recognisable as music. What actually happens is that the player app will be doing the MP3 conversion, generating a CD-like digital stream called PCM. It’s this PCM stream that the Niffy will be turning into analogue. FLAC is similarly pre-decoded.

Apologies to audiophiles, who will, of course, know all this already. But if you’re new to digital audio, we have a Data Sheet on the various formats that might be worth a visit.

The Niffy can handle pretty much all of these. And—most notably—the newest audio compression format, MQA. We cover MQA in a separate Data Sheet here.

But What Does the iFi Niffy Really Do?

At its simplest, you can think of the device as a DAC with a built-in pre-amplifier. Amplifiers need electrical power (DACs do too) and this is drawn primarily from the USB input at the rear when it’s connected to a computer.

But the power is supplemented by a built-in rechargeable Lithium-polymer battery and this feature allows the device also to be used with something like a phone or a tablet, less able to provide external power.

The digital input is through a USB type A connector. Note that this is an embedded plug, not a socket, so the cable you use to charge your phone won’t fit.

iFi provides a USB 3 cable that will take care of connecting to a computer. But for a phone connection, you’ll need an official OTG (on the go) USB adapter. Be aware that third-party cables are often designed on the assumption that you’ll be plugging a regular USB A connector into them (the sort that USB memory sticks use) and if the casing around the USB A end is too thick it won’t fit into the recess.

Once wired up, the Niffy replaces the internal sound system of your computer, phone or tablet with what the manufacturers claim (very likely correctly) will be a superior audio handling technology. The DACs used in standard phones and computers are generally not listed on the specs and are very likely to be generic, low-cost components that do the job with no particular finesse. The Niffy, on the other hand, is kitted out with a Burr-Brown 1793 Bit-Perfect DSD & DXD DAC chip that is revered by audiophiles and often turns up in equipment many times the price.

Once wired up, the Niffy replaces the internal sound system of your computer, phone or tablet with what the manufacturers claim (very likely correctly) will be a superior audio handling technology. The DACs used in standard phones and computers are generally not listed on the specs and are very likely to be generic, low-cost components that do the job with no particular finesse. The Niffy, on the other hand, is kitted out with a Burr-Brown 1793 Bit-Perfect DSD & DXD DAC chip that is revered by audiophiles and often turns up in equipment many times the price.

Audio engineers will tell you that the quality of the DAC chip is only part of the story. Getting the power supply right and devising a clean analogue output stage are crucial to overall performance. iFi seems to have paid special attention to this, improving on its earlier Nano iDSD, now offering a cleaner power supply and more powerful headphone output—ten times the power output of an iPhone 6, according to the manufacturer.

In fact, there are two headphone outputs, marked Direct and iEMatch. You can’t use them simultaneously but they give you a choice of, respectively, a clean output suited to most regular headphones and a resistor-damped output intended to improve the dynamics and reduce the hiss that can be associated with sensitive audio output devices like in-ear monitors (IEMs).

There’s an additional pre-amp output at the rear of the casing, a 3.5mm jack socket. As it’s designed to feed analogue audio into an external amplifier, unlike the two front 3.5mm jacks, the level of this output isn’t affected by the volume control.

Feeding the Niffy

DSD and some of its various sampling variations (DSD128 and DSD256—but DSD512 is a bit too rich for it) aren’t the only input formats the Niffy can handle. You can feed it pure PCM and DXD up to a sampling rate of 384KHz, and, of course, FLAC compression will be expanded prior to arriving at the Niffy.

If these names don’t mean much to you, you can bone up on them on our Data Sheet: Recorded Audio Formats. Which barely mentions what iFi sees as the key selling proposition.

Yes, it’s the controversial new format called MQA.

Master Quality Authenticated

This sort-of-lossy-but-not-so-you’d-notice compression format was pitched to the audio industry at the Consumer Electronics Show in Los Angeles in 2015. You can read more about it in our Data Sheet: MQA. The Niffy can handle MQA, but only as a renderer, which is to say that it needs the heavy lifting, the actual decoding, done externally on the device it’s attached to, either a computer or a smartphone.

In principle, this decoding half of the MQA operation is much the same thing as your software is already doing with MP3 and FLAC. But a lot more shifty.

The Niffy uses an MQA-certified Burr Brown 1793 DAC. Knowing this, the MQA organisation says it’s able to guarantee control over the entire transport between the analogue sounds created in the studio and the analogue signal emerging from the iFi nano iDSD Black Label DAC whenever it’s handling MQA. This, in fact, is the A for Authentication in the initials.

The Niffy uses an MQA-certified Burr Brown 1793 DAC. Knowing this, the MQA organisation says it’s able to guarantee control over the entire transport between the analogue sounds created in the studio and the analogue signal emerging from the iFi nano iDSD Black Label DAC whenever it’s handling MQA. This, in fact, is the A for Authentication in the initials.

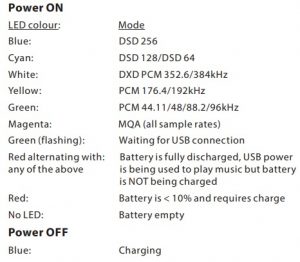

Which is when the magenta light goes on.

The Authentic Colour is Magenta

A Blue light when the unit is switched off shows that its battery is charging. If the LED shows steady Red when the unit is on, the battery’s running low and needs recharging.

Yellow or Green indicate that a pure PCM signal is being handled, the particular colour showing the sampling rate (see chart). So CDs will show up as Green.

Cyan or Blue indicate various DSD sampling rates, with White reserved for DXD. If any of these are alternating with Red, the battery has run flat and isn’t being recharged.

The star of the show is Magenta. This is the authenticating indicator that an MQA stream or file is being processed. What you’re hearing is the precise reproduction of the sound that left the studio…

The Analogue Hole (and others) in the MQA Argument

This is what many audiophiles will do. Especially, of course, when the unit is being used portably with a smartphone.

I suppose the point I’m making here is that the iFi unit’s MQA won’t magically bring the world of the studio into your listening room if you’re rocking a budget amplifier feeding into a pair of indifferent bookcase speakers. (Which is not to say that the output won’t be enjoyable. But fidelity, not enjoyment, is what MQA is about.)

The Niffy in Action

on the computer

The first of the two computer apps is Tidal. It will unfold MQA, passing the decoded output to the Niffy. But you can’t use it to play any local tracks you may have—it’s strictly the front-end for the Tidal streaming service.

The desktop app, for Windows and Mac, is free, but the service will cost you £10 a month (actually £9.99, but are we still fooled by these pricing tricks?). For that you get the “Premium Service”, which despite the name offers only “standard quality” tracks. If you want HiFi and MQA you’ll need to double your subscription to £20 a month.

The second desktop app, also running on Windows and Macs, is Audirvana Plus, (so-called, perhaps, because it aims to be the audiophile’s Nirvana). At just under £70 (for the Mac version—the Windows version is still in beta) Audivana Plus isn’t cheap. But a great deal of work has gone into providing what the vendor claims is “Ultimate Sound Quality”.

Audirvana Plus operating as a Tidal client.

The audio handling software provided by the operating system, like the audio hardware, will typically be “just about good enough”. In the same way that the Niffy cuts out your computer or phone’s generic DAC, Audirvana Plus can take over core functions like upsampling. It can also take exclusive control of the audio output and optimise for audio playback by adjusting its priority over cycle-stealing background system functions and, in the case of Spotlight indexing and Time Machine backup, suspending them completely.

Audirvana Plus will play your computer’s local music tracks, and also handle collections from across your LAN—for example, from a NAS. It can also reach out across the Internet to a couple of streaming services. One of these is Tidal and the other is Qobuz. Audirvana Plus users get a free three month subscription to both these thrown in.

With version 3, released in March of this year, Audivana Plus became the first MacOS music player able to decode MQA. My long-standing favourite Mac music app is JRiver’s Media Center. But JRiver CEO Jim Hillegass has gone on record as saying: “JRiver has no plans to support MQA. MQA is not a lossless or open format, and it offers no apparent benefit to consumers, in our opinion.”

on the phone

The Android app I’ve been using to test the Niffy is Neutron. Priced at a very modest £5.49, Neutron may even more of an audiophile’s Nirvana, with a user interface that is bristling with options and really needs a three-day seminar to get on top of. Audivana Plus seems to be aiming mostly at fidelity and purity of reproduction. Neutron, on the other hand, appears to be based on the hypothesis that whatever input you’re dealing with will need equalising, mixing, converting and generally being massaged with digital signal processing.

The Android app I’ve been using to test the Niffy is Neutron. Priced at a very modest £5.49, Neutron may even more of an audiophile’s Nirvana, with a user interface that is bristling with options and really needs a three-day seminar to get on top of. Audivana Plus seems to be aiming mostly at fidelity and purity of reproduction. Neutron, on the other hand, appears to be based on the hypothesis that whatever input you’re dealing with will need equalising, mixing, converting and generally being massaged with digital signal processing.

In this spirit, it seems, Neutron doesn’t handle MQA. But it’s excellent for sending PCM or DSD bitstreams to the Niffy. Or even without the Niffy, using the phone’s own generic DAC.

Inevitably, though, this does raise the question of the Niffy’s use as a portable device. The retail package comes with a pair of stout neoprene elastic bands you can use to bind the device to the back of your phone. The combination is bulky and pocket-unfriendly and I’m not sure I’d want to travel like that. Adding the fact that you won’t get MQA out of the combination (not at the time of writing, although MQA rendering phone apps are said to be on their way) suggests you’d have to be seriously keen on hi-res to want to do this. And then probably only as an interim fix until you can get your hands on a dedicated MQA portable music player.

Back to the Desktop

As an external DAC supplementing a Mac or PC, with software like Audirvana Plus taking control of the internals, the Niffy makes a lot of sense. Particularly if the output is going into seriously good IEMs, headphones or an external amp. If you’re not bothered about MQA, the JRiver Media Center, able to handle DSD, would be another candidate.

The reality is that a greatly improved DAC, drawing on a well-regulated, noise-free power supply and playing out through a carefully designed analogue pre-amp—as in the Niffy—should certainly give you cleaner, less error-prone music.

And it will probably more accurately carry any ultrasound the studio producer intended to include. Whether that ultrasound reaches your cochlea through your analogue equipment is another matter. Even if it does, equally moot is the question of whether your cochlea will be able to make anything of it.

And it will probably more accurately carry any ultrasound the studio producer intended to include. Whether that ultrasound reaches your cochlea through your analogue equipment is another matter. Even if it does, equally moot is the question of whether your cochlea will be able to make anything of it.

You might also want to look at the other end of the reproduction chain and ask that (probably) middle-aged studio producer whether his or her audiogram demonstrates the slope off at around 4kHz that typifies age-related hearing loss (ARHL).

Yes, that’s more than two octaves below the 20kHz upper limit for CDs which is the starting point for this hi-res stuff.

It’s really important to note here that better quality music listening isn’t just (or perhaps at all) about extended frequency. In an intelligent discussion of the subject—well worth reading in full—monty@xiph.org touches on “golden ears”. (The original link has disappeared from the Web, but the article is still accessible thanks to the Wayback Machine.)

Young, healthy ears hear better than old or damaged ears. Some people are exceptionally well trained to hear nuances in sound and music most people don’t even know exist. There was a time in the 1990s when I could identify every major mp3 encoder by sound (back when they were all pretty bad), and could demonstrate this reliably in double-blind testing.

When healthy ears combine with highly trained discrimination abilities, I would call that person a golden ear. Even so, below-average hearing can also be trained to notice details that escape untrained listeners. Golden ears are more about training than hearing beyond the physical ability of average mortals.

Bottom line, whether it’s worth spending on audio equipment like the Niffy (around £200) is up to you and your ears. And here in the UK, the NHS will test them for free—as it did mine. That’s probably worth a thought.

Chris Bidmead