During the past several weeks with Panasonic’s Toughbook I’ve been waiting for a rainstorm. The plan was to include a photo of both of us out in the garden plugging away at this article and getting drenched.

The rainstorm hasn’t come. So instead I faked a pretty fair equivalent with a garden hose (see picture below). I hadn’t had permission from Panasonic to do this, but earlier this year I’d visited the factory in Kobe, Japan, where these things are made. There I’d seen the sort of soak-testing (the literally very wet kind as well as the metaphorical kind) Panasonic regularly treats its Toughbooks to.

I needed a change of clothes afterwards; all the CF-33 required was a good shaking and a bit of mopping up with a dry cloth. I’m proud to say we both performed flawlessly during the exercise.

Screen Test

IN PART 1 OF THIS REVIEW, I MENTIONED how I’d come to terms with the CF-33’s somewhat intransigent resistive trackpad. (One useful trick, I found, is to use a fingernail rather than the ball of your finger for both tapping and tracking.)

IN PART 1 OF THIS REVIEW, I MENTIONED how I’d come to terms with the CF-33’s somewhat intransigent resistive trackpad. (One useful trick, I found, is to use a fingernail rather than the ball of your finger for both tapping and tracking.)

Resistive technology, I learnt, is resistive in more ways than one.

Although the large capacitive touchpads in today’s Ultrabooks understand gestures with multiple fingers, they’re only fair weather friends—at least, according to conventional wisdom. Resistive technology, we’re told, remains much more reliable in extreme environments.

This seemed to be a clincher—until I discovered that Panasonic doesn’t apply this capacitive versus resistive argument to the 12″ IPS touch screen. At least, not any more.

Early Toughbooks used a resistive touch screen for the same reason as the touchpad. But back then apps designed for touch were a lot less sophisticated. One touch to launch an app; one touch to select a tick box.

Today’s touch apps presume much more sophisticated control. This persuaded Panasonic to use capacitive touch panels when they introduced their first Toughpad tablet in 2011, and the technology has since been carried over to the Toughbooks.

A capacitive screen needs careful tuning in a device designed for a range of harsh environments. Panasonic’s marketing manager Jon Tucker tells me: “We have a lot of control of the capacitive touch panel so we’re able to configure the characteristics to have different modes.”

For this reason, the screen also incorporates a quite separate electromagnetic technology. In addition to the capacitor array, there is a fine grid of tiny coils beneath the surface of the screen. These coils can be set each to generate an electromagnetic field.

The IP55-rated stylus holstered in the screen’s bezel has two on-off buttons, one at the tip that indicates whether the stylus is in contact with the screen, and one at the side that can be assigned as a right mouse button. The stylus needs no battery because its coils draw power from the electromagnetic fields emanating from the screen. This enables the stylus to feed back information to the tablet, not just about its location but also about the state of the two buttons, which switch in circuits that alter the electromagnetic resonance of the stylus.

The IP55-rated stylus holstered in the screen’s bezel has two on-off buttons, one at the tip that indicates whether the stylus is in contact with the screen, and one at the side that can be assigned as a right mouse button. The stylus needs no battery because its coils draw power from the electromagnetic fields emanating from the screen. This enables the stylus to feed back information to the tablet, not just about its location but also about the state of the two buttons, which switch in circuits that alter the electromagnetic resonance of the stylus.

This is Panasonic’s “digitizer mode”, which ignores fingers completely.

Panasonic’s PC Settings Utility allows you to select between using both the touchscreen and the digitizer, just the touchscreen or just the digitizer. You can also select between regular touchscreen operation and modes suitable for gloved and wet fingers.

Further technical details about the screen are here. (Note that the Transflective Plus technology mentioned here isn’t incorporated in the CF-33.)

The Power Behind the Screen

Batteries run out on you. They run out day to day, and over time they run down altogether. The fashion in these days of slim Ultrabooks and skinnier than ever phones is to embed the battery deep in the casing. Sometimes these batteries can be swapped out by a service engineer, but sometimes they’re even glued in solidly, destined for the recycling bin along with the rest of the device.

Batteries run out on you. They run out day to day, and over time they run down altogether. The fashion in these days of slim Ultrabooks and skinnier than ever phones is to embed the battery deep in the casing. Sometimes these batteries can be swapped out by a service engineer, but sometimes they’re even glued in solidly, destined for the recycling bin along with the rest of the device.

Panasonic’s Toughbooks preserve the tradition of allowing the untechnical user to flip out the battery and slap in a replacement in a matter of seconds. In fact, the CF-33 takes this a step further, with a pair of batteries, either of which can be hot-swapped in mid-operation.

On full charge the batteries give an estimated average of 11 hours running time. Extended batteries are available that stretch this to 22 hours.

Obviously, battery running time will depend on usage, and, especially in the case of the CF-33, on external conditions. For example, the fan built into the screen section will need to run faster in hot surroundings. To be readable in bright sunlight, the screen backlighting will need to come up full blast.

When I visited the Toughbook factory in Kobe, Japan earlier this year✽, I was given the opportunity to assemble part of the Toughbook motherboard. One of the components I was required to install on top of the solid state drive (SSD) was a flat resistance coil printed on a thin, transparent plastic sheet. This was the SSD heater.

Why is an SSD like a bucket of water? Because at 0 degrees Centigrade they both freeze. A typical SSD just stops working when the temperature drops that low. To maintain the Panasonic promise of continued operation right down to -29 degrees Centigrade, that SSD heater needs to kick in. That’s going to use extra juice.

Keeping the Electrons Moving

With battery consumption varying with the environment like this, the ability to hot-swap in a pair of replacements is crucial. Some serious design thought has been applied to this process.

With battery consumption varying with the environment like this, the ability to hot-swap in a pair of replacements is crucial. Some serious design thought has been applied to this process.

Historically, swappable laptop batteries tended to be weird shapes. This six-cell Lenovo battery (pictured) is typical—you wouldn’t want to lug many of those about with you.

The standard CF-33 batteries are slim rectangles, with only two small protruding lugs on either side of the electrical connector. I could carry a couple of them in my trouser pockets and four more in my various jacket pockets without my tailor raising an eyebrow.

The two batteries fit into a compartment behind the screen. Although waterproof, the lid can quickly be slid open and a battery swapped out in under ten seconds. As long as the batteries are exchanged sequentially, the machine will keep going without missing a beat.

To ensure charged spare batteries are always available the system will need to include a separate battery charger. Panasonic’s price for this accessory would cover the cost of the average office notebook. But the whole point of the Toughbook is that you pay up front to save over the long term. Or if you’re out in the Arctic with those Huskies, you pay up front for something that keeps the electrons moving where nothing else will.

The Not-Quite-Presentation of the Toughbook

✽Speaking of the Kobe factory, I can’t help mentioning the Toughbook Presentation Incident.

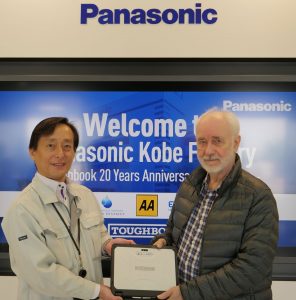

We European visitors walked in through the front door, swapped our shoes for slippers the way we’d become used to in Japan, and checked in at reception. Before going onto the factory floor, we were invited to line up one by one to be greeted by the Chief Manager, Mr Minoru Shimizu.

This turned out to be no mere handshake. I found myself being presented—as it seemed in the moment—with a Toughbook.

I’ve been on factory visits many times before, but not in Japan. In Europe you do get offered products to take home—a keyboard, perhaps, or a calculator. But here I was, with the official Panasonic photographer snapping away, as Mr Minoru handed me a solid, real-life, three-grandsworth of computing ruggedness. How would this affect my upcoming review? I would obviously have to level with my readers…

I’ve been on factory visits many times before, but not in Japan. In Europe you do get offered products to take home—a keyboard, perhaps, or a calculator. But here I was, with the official Panasonic photographer snapping away, as Mr Minoru handed me a solid, real-life, three-grandsworth of computing ruggedness. How would this affect my upcoming review? I would obviously have to level with my readers…

In the event, once the photo was taken, Mr Shimizu retained the Toughbook for repurposing with the next guest in the queue. Clearly I’d taken part in some purely symbolic ritual. Or was it possible we were being spared having to lug the device around for the rest of the trip, and the gift would be ours at the end of the visit?

I dismissed the thought from my mind. This would have to be some Japanese mode of greeting I was culturally ill-equipped to understand.

But the memory, I must confess, stayed with me. The Japan trip, around offices, temples and shopping centres, had been regularly punctuated by pauses for official group photographs, complete with the unfurling each time of the celebratory “20 Years of Toughbook” banner. The Kobe factory Toughbook not-quite-presentation seemed like an odd tease.

There was, as it turned out, a closely related gift in my hotel room at the end of the trip. It was a Toughbook-shaped framed copy of that presentation photograph.

There was, as it turned out, a closely related gift in my hotel room at the end of the trip. It was a Toughbook-shaped framed copy of that presentation photograph.

More to Come

Having said that, Panasonic hasn’t skimped on the time it’s allowed me to review this CF-33. Before I finally part with it, I should probably touch on the software side of the machine. So in the next installment I’ll be winding up with some conclusions about how the device works as a whole.

Chris Bidmead