A couple of months ago I slipped a mention of the new AZIO Retro Classic Keyboard into my review of the Varidesk ProPlus 36, telling you I’d follow up when the Bluetooth version of that keyboard arrived. This is that promised review.

Keyboards have been much in the news of late, largely on account of manufacturers like (and also mainly) Apple. In the race towards ever thinner, ever lighter laptops, designers have been taking risks around the mechanics of the keyboard, offering ever shorter key travel and flimsier action. Recent MacBooks, in particular, have been accused by users of being susceptible even to tiny dust particles, to the extent that individual keys can become unreliable or even fail altogether.

These are not the keyboards I was brought up on. Although my writing history doesn’t date back as far as the classic Underwood No 5 that kicked off the 20th Century, the keys I clacked in my earliest days as an author belonged to typewriters that drew inspiration from that old perennial best-seller. The desk typewriters were mighty and even the portable machines of the mid-20th Century had heft, travel and clack. Conflicting type levers might occasionally jam against one another if you typed too fast. But those tap-dancing keyboards laughed off everything from dust to fat crumbs of toast.

When I started to tackle computers in the late ’70s, the keyboard champion was Cherry. Metal by now was mostly replaced by plastic. Your 1970s Cherry was beige but solid, the keys travelling into a hard stop with a distinct crisp thud. You didn’t need to see the glowing green ASCII characters coming up on the black screen to know you were typing. The whole room could hear you were hard at work.

Although the racing progress of Moore’s Law obsoleted your desktop computer almost annually, those Cherry keyboards out-lived many generations of central processors. Well, guys, the good news is… those happy days could be back with us.

CHERRY IS STILL MANUFACTURING its line of robust mechanical plastic keyboards, of course. They’re widely used with business desktops and much appreciated by gamers, who demand decisive responsiveness and reliability. But the AZIO keyboard under review here takes the idea of the mechanical keyboard a whole stage further. Or should that be “a whole century back”?

CHERRY IS STILL MANUFACTURING its line of robust mechanical plastic keyboards, of course. They’re widely used with business desktops and much appreciated by gamers, who demand decisive responsiveness and reliability. But the AZIO keyboard under review here takes the idea of the mechanical keyboard a whole stage further. Or should that be “a whole century back”?

The overall visual effect is a bit like stepping into a steam-punk movie. Two major anachronisms would instantly strike the typist of 1900: the rows of keys are flat, not arranged in steps; and each individual key is glowingly backlit. Those two differences apart, the experience of using the AZIO is very like typing as I remember it from the 1960s. And it’s great to be back!

Setting Up the AZIO Retro Classic

This Bluetooth keyboard needs to be charged—for about 6 hours—before it’s ready for Bluetooth connection. I did this by wiring it to my Mac with the provided USB cable. The USB socket on the keyboard is type-C. There’s nothing particularly fancy about this, the only advantage in this case being that you don’t have to think about which way round the connector goes.

It appears that the keyboard can’t be used, even wired, until the built in rechargeable 6000mAH battery approaches capacity. I felt I should have been able to use the keyboard in cable-attached mode during this period, but I couldn’t find out how to do this.

Once the keyboard was charged, I removed the cable and paired it with the Mac’s Bluetooth. This wasn’t entirely straightforward. Switching the keyboard to Bluetooth using the mechanical switch at the rear doesn’t automatically put it into pairing mode (which I thought was strange). Instead, you need to hold down the Function Key and the Minus key on the numeric keypad. The W indicator on the keyboard flashes slowly to indicate this mode.

Once the keyboard was charged, I removed the cable and paired it with the Mac’s Bluetooth. This wasn’t entirely straightforward. Switching the keyboard to Bluetooth using the mechanical switch at the rear doesn’t automatically put it into pairing mode (which I thought was strange). Instead, you need to hold down the Function Key and the Minus key on the numeric keypad. The W indicator on the keyboard flashes slowly to indicate this mode.

The Mac found the keyboard quickly, first identifying its MAC address and then replacing that with “AZIO Retro Classic BT”, the ident also offering an on-screen Pair button.

But we weren’t done yet. The screen also showed a six-figure pairing code I was required to type out on the keyboard. I was puzzled when my first three attempts were greeted with a failure message.

The AZIO Retro Classic Bluetooth keyboard, like the USB keyboard, has a numeric pad on the right-hand side, as well as the regular typewriter-style numeric row across the top. Which would you have used to enter the numeric Bluetooth pairing code? It turns out the digits have to be entered using the numeric top row keys.

The AZIO comes with a set of spare keycaps which you can use to adapt the keyboard to full Mac status, once you’ve set the toggle switch at the rear from PC to Mac. Although I was using the keyboard with a Mac I didn’t initially find this conversion necessary—the Mac software adapts itself nicely to various standard PC keyboards.

The AZIO comes with a set of spare keycaps which you can use to adapt the keyboard to full Mac status, once you’ve set the toggle switch at the rear from PC to Mac. Although I was using the keyboard with a Mac I didn’t initially find this conversion necessary—the Mac software adapts itself nicely to various standard PC keyboards.

After making the Bluetooth connection, the Mac announced that it didn’t recognise the (unadapted) keyboard and asked me to tap the key immediately to the right of the shift key. When I did so MacOS automatically installed the correct keymap and the keyboard became almost fully useable straight away.

I say “almost” because just two of the more exotic keys got their identities interchanged. This didn’t bother me at all right away. And when it eventually did, an easy remedy was at hand in the shape of Ukelele, a veteran third-party free software Mac app that makes it very easy to edit one of the many available standard Apple keymapping files to exactly tailor whatever keyboard you happen to be using.

Or, of course, I could just have swapped over the push-on-pull-off keycaps.

From Logitech to AZIO

Initially, the changeover from the cheap but serviceable, near-silent plastic Logitech wireless keyboard I’d been using to this new luxury metallic KlackMeister took a fair bit of adjustment. My office chair needed to be higher, as the AZIO has a rather taller profile on the desk. Its slope is adjustable to a limited extent by turning the two copper coloured rings that house the rear feet. I found the keyboard worked best for me with these both fully extended. Of course, the result, even at maximum slope, is nowhere near the steeply tiered keyboard of a mechanical typewriter.

The AZIO keyboard has “desk presence” like the “wrist presence” admired by watch enthusiasts.

Coming to this from the Logitech, the touch is quite different—a very positive, old-fashioned, full-travel action accompanied by a distinct click at each depression. Once I got the hang of this, (my amateur) touch-typing at speed turned out to be no problem. For the professional typist, the two traditional raised bumps on the F and J keys are there for the left and right index fingers to establish the home position of the hands without even a downward glance.

Most wireless and Bluetooth keyboards I’ve encountered are lightweight affairs, easy to push to one side or lift out of the way if you want to clear your desk for something other than typing. The AZIO, on the other hand, majors on what you might call “desk presence”.

I’m borrowing the phrase from wristwatch enthusiasts, who tend to attribute the term “wrist presence” to any enormous shiny divers watch. This particular heavy copper and leather device is not shy to make itself thoroughly at home at the foot of your screen, but can also on occasion dominate the room.

I’m not exaggerating. Several visitors to the Tested Technology office in recent weeks have immediately lighted upon one or other of the two AZIO Retro Classics glowing smugly on my regular desk or the sit-stand desk and immediately moved in to investigate.

AZIO Technology

Cherry was established in 1953 by Walter Cherry in the basement of an Illinois restaurant. In the spirit of Trump’s tendentious “Make America Great Again” you might expect AZIO, an American “manufacturer of computer and electronic peripherals”, if not actually making its own components, would be sourcing them at least nationally. But the AZIO keyboards are manufactured in the same place that makes the Trump range of ties.

Kaihua Electronics has been around for less than thirty years, but appears to be a respectful, innovative inheritor of the Cherry tradition. I gather there’s been some kind of (entirely legal) technology transfer here, on top of which Kaihau has developed over a hundred of its own patents. While Cherry remains, in the eyes of many gamers and touch typists, the mechanism of choice in keyboards like the all-Cherry Das 4 Professional, the Kailh brand runs neck-to-neck with it.

Why Bother with an AZIO Keyboard

You can pick up a regular wireless keyboard for less than £10. So why on earth would you want to pay around £170 for the wired AZIO I mentioned in my previous review or in excess of £200 for this Bluetooth version? (The Bluetooth version launches in the UK next month, and isn’t yet listed on the Amazon UK Website. I’ve been quoted a price of $219.99 which I expect will translate to roughly the same figure in sterling.)

You can pick up a regular wireless keyboard for less than £10. So why on earth would you want to pay around £170 for the wired AZIO I mentioned in my previous review or in excess of £200 for this Bluetooth version? (The Bluetooth version launches in the UK next month, and isn’t yet listed on the Amazon UK Website. I’ve been quoted a price of $219.99 which I expect will translate to roughly the same figure in sterling.)

If you’re like me, you spend a lot of time at the keyboard. You want one that lasts, and, more importantly, perhaps, one that’s a joy to use. For me, the AZIO Retro Classic has turned out to be exactly that.

Or maybe it’s just nostalgia…

“I never got along with the computer screen”, says the American playwright Sam Shepard in the documentary California Typewriter (a must-see for any writer). “It’s somehow removed from the tactile experience”. For Shepard, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and actor who died last year, it had to be paper, the rolling platen and, of course, the mechanical keyboard.

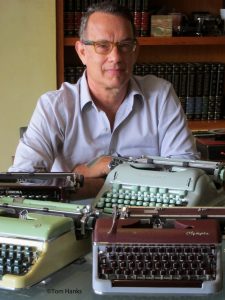

Actor Tom Hanks is an avid—one might say obsessional—collector of vintage typewriters. In the documentary he agrees with Shepard about the typewriter. “It actually turns writing… into a very specific physical process—that has a soundtrack to it”.

This certainly chimes with me. I have to confess that my favourite keyboard of all time has of late been the Gboard virtual keyboard I run on all of my Android phones. It’s difficult to imagine anything so remotely different from this than the two AZIOs I’ve been using consistently over the course of this review. (Full disclosure: AZIO has kindly agreed to leave both keyboards with us for extended testing).

| Gboard |

AZIO |

| “Glide typing” lets you write a whole word with a single gesture. | Every word has to be spelt out letter by letter. |

| I needn’t be at a desk. I can write an entire article stretched out on the sofa. Or on top of a bus. | Confines me to my work desk. |

| Can be completely silent (but see next item). | A loud clack with every keystroke. |

| I can switch in and out of dictation almost seamlessly. | Fingers only operation. Think-Type (no talking). |

It’s tempting to read this as a table of pros and cons. But any writer with serious work to be getting on with would see that it’s actually a table made up of cons and pros. The Gboard keyboard offers a seductively leisurely approach to writing. The AZIO, on the other hand, gets you really taking care of business.

It’s tempting to read this as a table of pros and cons. But any writer with serious work to be getting on with would see that it’s actually a table made up of cons and pros. The Gboard keyboard offers a seductively leisurely approach to writing. The AZIO, on the other hand, gets you really taking care of business.

But I have to agree with Shepard and Hanks about the tactile experience of writing. A decent mechanical keyboard turns a writing session into an occasion.

Writing—real writing—is tough. It requires discipline. Lazy writing is very easy, chiefly because it leaves all the work to the reader. If the reader can be bothered.

I used to think that any gadget that helped me fill in the odd ten minutes waiting for a train, or let me jot down my thoughts in the back of a taxi, or that I could reach for in the middle of the night to capture my next brilliant idea, would turn out to be my ticket to a Pulitzer Prize. That all those broken bits of time would join up into a fast-flowing best-seller.

And now that gadget has arrived. It’s the mobile phone.

The novelist Cory Doctorow once assured me that you can indeed write a book like this. Experience tells me otherwise. The “crumbs of time” approach is great for taking notes, but notes won’t meld magically to create your next magnum opus. Most of the notes you take like this will wither into oblivion.

What, if anything, will last is prose that flows from multiple, disciplined, sustained work sessions. Stephen King (among others) calls this being “in the zone”. Typically at a desk. You may not enjoy the work of writing, but you should at the very least enjoy the desk. And all the writing appurtenances thereof. The coffee cup. The screen. And, of course, the keyboard. The specific physical process and—as Tom Hanks says—the soundtrack that goes with it.

True, there’s no ding at the end each line these days (and, come to that, no line-endings at all), but the AZIO keyboard at least restores the tap-tap-tap in its full glory. Connected to my computer, it gives me the best of both worlds.

Chris Bidmead