Joni Mitchell writes great songs with insightful lyrics.

“Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got til its gone…”

It took a disaster to kick me into doing this review. Note to manufacturers: if you want to show up in this publication don’t make your products so good that they disappear from view the moment they’re installed. And only become visible when things go wrong. (I’m kidding. A good WiFi infrastructure should be invisible. I’ve learnt my lesson.)

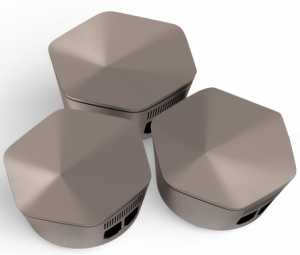

The Plume Superpods are masters of invisibility. You plug them into the wall, wait twenty minutes for them to self-configure and there you are with fast WiFi throughout the house for the foreseeable future. Set and forget.

Which is what I did.

Until that disaster* I mentioned.

We’ll come to that part of the story later…

ONE OTHER REASON FOR THE delay to this review was confusion about what it actually was that we were reviewing here at Tested Technology. I was at the launch in March of 2019 and the reviewer kit we received subsequently comprised three devices called Plume Superpods.

Consumers here in the UK were being sold a set of three very similar-looking Plume devices. But only one of them would be a Superpod. The other two, apparently rather less capable, were called Powerpods.

So what was a Powerpod and how did it differ from a Superpod?

It was a question—rather crucial to a review, we thought—that was only satisfactorily cleared up months later.

What you do not know is the only thing you know…

But, in truth, the chief reason I didn’t rush to write this review until over a year later is a little more nuanced. You’ll have noticed, if you’ve read at least a couple of the reviews here, that we don’t just echo what the manufacture wants to tell the market. Or merely chronicle our experience of the product.

It’s important for us to understand—at least at some level of technical depth—how the magic works.

And when it came to the Plume setup, frankly, I didn’t. And still don’t. During the course of writing this review I hope to learn more.

Ever since that press launch I’ve been trying to make some sense of what is actually going on with these strange, silvery, hexagonal devices that each look just a touch too big to plug into one side of UK double mains socket while allowing room for a second plug beside it.

(Surprise—there is enough room!)

I never intended to get up to my elbows in the technology. But I wanted to understand it well enough to be able to explain something of its workings to our readers.

Yes, I’m contradicting myself. I began by saying I had forgotten the three Plumes while they silently get on with their jobs. And now I’m telling you I’ve been obsessing about how they do that.

Well, it’s both at once. In much the same way as the Master of the House may have taken the servants for granted (with the servants themselves striving to maximize efficiency and invisibility) at the same time as wondering what was really going on below stairs… that more or less sums up me and the three Plumes.

The three Plumes are evidently what they look like, entities from beyond this planet. In Arthur C. Clarke’s famous formulation:

The three Plumes are evidently what they look like, entities from beyond this planet. In Arthur C. Clarke’s famous formulation:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic

…which, of course, exonerates me from any need to understand what’s going on below the hood.

You think?

Any item that is sufficiently orange becomes invisible, Arthur tells me. Really, I say? I point to a bowl of oranges. Does it look empty? Ah, replies Arthur, the oranges are certainly orange. But they are evidently not sufficiently orange.

What Plume Does

Ever since I discovered that on the Continent, they refer to it as Le “Wiffy”, that’s how I’ve been pronouncing it. Appropriate, because in many cases WiFi can be just that. Fine in the living room, but up in the study you’re just getting the merest whiff of it.

If this is you and your study, Plume could be just what you’re looking for.

There are innumerable WiFi extenders and interconnecting systems for spreading your WiFi goodness around the house. I’ve experienced many of them. Some are slow (which might not matter, if you’re trying to extend into a room where you only do the odd bit of googling and WhatApping). Several are perilously complicated to set up. Many spend too much time fighting off interference from neighbouring WiFi to give you optimum service.

Plume seems to have cracked these problems. But let me see if I can get to grips with the basics of how all these various makes of WiFi extenders approach the job.

Spread the Router Goodness

To start with, you obviously need an existing piece of equipment, usually supplied by your Internet Service Provider (ISP), that connects you into the Internet. The Internet is out there on a Wide Area Network (WAN) and this device provides you with a means to connect the WAN with the Local Area Network (LAN) around your house. Because it’s routing Internet information in and out of your LAN to and from the WAN, the device is called a router.

A router doesn’t necessarily have to be able to radiate WiFi but these days most consumer routers have this feature, becoming WiFi Access Points (APs). You should be able to turn off the router’s WiFi and it’s often desirable to do so. We’ll come to that later.

Initially, you may not have a LAN. Your laptop or desktop computer may be the single device connected to the Internet through the router. Strictly speaking, this is still a LAN, a special case of a LAN with only two devices on it: your computer and the inward-facing half of the router.

It’s usually only after you have several devices to connect to the Internet that you begin to wonder if there might be a better way of doing things. You can wire several of them directly to the router, as routers are provided with Ethernet ports, four ports being typical. Running Ethernet cable from your router to each and every device on your LAN is usually the best engineering solution to the problem of distributing the router’s capability around the house. In fact, this is what I did in the early-90s when the Internet started getting interesting.

16-Port TP-Link Switch as used in the Tested Technology office.

The termination of an Ethernet cable wired to your router needn’t be a single computer. You can add an Ethernet switch which turns that single Ethernet connection into multiple connections. With Ethernet switches installed this way, all your computing devices with Ethernet ports can be talking to your router at the best possible speed.

But…

There are a couple of “buts” here.

- Knocking holes in walls and strewing cables along corridors is frowned on in our family and probably is in yours too.

- Many of the things that need connecting to the Internet these days don’t have Ethernet ports. Our smartphones, our ultra-light notebooks and (increasingly common now) our fridges and washing machines, all depend on WiFi to join our LAN.

Point 2 is easily dealt with. Instead of a simple Ethernet switch, you just use an Ethernet switch equipped with its own WiFi Access Point. Much like your typical router. In fact, every WiFi router I’ve come across can double as a WiFi-equipped Ethernet Switch. That way you get WiFi everywhere around the house.

If you’re OK about the wiring.

Point 1 is usually the stumbling block here. Those wires joining the various Access Points around the house form the backbone of your network. Or what’s known in the trade for historical reasons as the backhaul.

So the question becomes, how do we lay down a backhaul without the wiring?

The two principle ways of doing this are:

- Use WiFi (duh!)

- Use the existing electrical mains wiring that runs through the house (clever!)

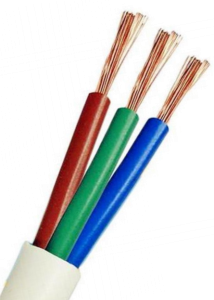

The second approach, Powerline networking, can be very impressive. Copper wires that were laid down, invisibly within the structure of your house perhaps decades before the arrival of the Internet, reaching all the rooms, designed to carry a lot of electrical current with voltages alternating in the mid-100Hz range, can be repurposed to convey Internet information with very low current using voltages that alternate orders of magnitude faster. At the same time as feeding you regular electricity.

The second approach, Powerline networking, can be very impressive. Copper wires that were laid down, invisibly within the structure of your house perhaps decades before the arrival of the Internet, reaching all the rooms, designed to carry a lot of electrical current with voltages alternating in the mid-100Hz range, can be repurposed to convey Internet information with very low current using voltages that alternate orders of magnitude faster. At the same time as feeding you regular electricity.

And the wiring doesn’t need to be continuous, either. Provided the wires are close enough, information carried this way can jump from one set of wiring to another. The arrangement works well for slowish connections and, with luck—depending on the nature of your mains wiring—can even compete with other backhaul methods. If you live in a stone castle with walls virtually impermeable to WiFi, this may be your only option.

The obvious way, WiFi for the backhaul, is full of perils.

The obvious way, WiFi for the backhaul, is full of perils.

Domestic WiFi operates in two separate frequency spectrums, 2.4GHz and 5Ghz. The lower frequency spectrum, 2.4GHz, isn’t too bad at passing through solid walls and can travel longer distances than the 5GHz spectrum. But it’s very crowded as it will be widely used by your neighbours. And their microwave ovens.

The higher frequency 5GHz spectrum has the disadvantage of being much more easily blocked by obstacles and can’t reach as far. But it also has the advantage of being more easily blocked by obstacles and not being able to reach as far. That is to say, in this spectrum you’ll get less interference from neighbouring WiFi. A cleaner signal that can carry data significantly faster.

WiFi as a backhaul has some decent potential. But there’s a lot of calculation to be done—and to be done continuously on the fly as the WiFi environment around your house is continually changing. Ordinary WiFi extension arrangements don’t bother with this. Plume is an exception.

AI to the Rescue

A lot is happening in and around your WiFi installation. Some of it will be reasonably constant—the distance and signal strength between your various WiFi access points, for example. Some of it will vary on an approximate schedule, like the additional load when you sit down to watch Netflix in the evening. And some of the variability may be unpredictable, like WiFi interference from your neighbours’ installations. Even the changing humidity of your brickwork can affect signal strength.

A lot is happening in and around your WiFi installation. Some of it will be reasonably constant—the distance and signal strength between your various WiFi access points, for example. Some of it will vary on an approximate schedule, like the additional load when you sit down to watch Netflix in the evening. And some of the variability may be unpredictable, like WiFi interference from your neighbours’ installations. Even the changing humidity of your brickwork can affect signal strength.

The various things you’re using to connect to WiFi have their individual characteristics, too. According to current WiFi standards, you should be able to use exactly the same password and SSID (the Service Set Identifier—the name that is being broadcast by the WiFi AP) for each of the WiFi extensions around the house. In theory, you can then travel from room to room and from floor to floor without having to reset your smartphone’s WiFi connection.

The goal is that your client device, your phone or laptop, sensing that it’s losing the original signal, detects a new, stronger signal using the same SSID and automatically latches onto that without you having to do anything or even know about it.

This neat idea, on-premise WiFi roaming, works with some client devices but not with others. Historically, Android smartphones have been notoriously keen on clinging to their original WiFi AP even as the signal weakens to invisibility while a second, nearby, strong AP clamours to offer assistance. In the past, I often wondered why I needed to reset my Android WiFi as I moved around the house.

If you move into another room with a tablet, say, that remains glued to an inappropriately weak signal, it may be that it’s a device the Plume database doesn’t yet know about.

You can usually fix the problem by switching the device’s WiFi off and on again.

Plume has solved that for me. It knows the characteristics of the various connecting devices and has a playbook of techniques and tricks needed to handle them optimally. And it can also sniff out all these constants and variables we were talking about.

But the storage requirements to contain these data—as well as the compute power needed to make useful sense of them—is a great deal to ask of a small, warm but not too hot device like a Plume Superpod.

Fahri Diner, co-founder and CEO of Plume told me at the launch event this was a problem that would have been impossible to tackle ten years ago when he started thinking about it. It’s one thing to have hopes and dreams, it’s another (non-trivial) thing to do the maths and design the logic to fulfil those dreams. And to build a practical device that actually implements all that is something else altogether.

Today you don’t have to do all that storage and computing inside the device. Today, distant server farms comprising as much storage as you need with compute power to match can do all the heavy lifting.

Plume’s small plug-in pods collect the information needed to optimise your WiFi. But the data management and smart thinking take place out there in the Cloud.

Which, of course, raises an important question… If your data is being used out in the Cloud, how secure is Plume.

We’ll get onto that in part 2. And we’ll reveal all about the “disaster” that triggered this review.

Chris Bidmead