I’ve been writing about projectors for more than 10 years now, and it has been a delight to see the quality increase and the prices fall.

And, of course, the technological developments. But, in truth, I haven’t been all that enamoured by the move to ever higher resolutions.

Some years ago, I was telling readers that “720 is plenty”. Even on a 100″ projector screen, the resolution is enough to banish any blurring at the centre of focus while sufficiently softening any peripheral details that might be a distraction from the story.

Yes, I know this is controversial, and we’re all moving into a 4K world (and beyond). This review moves Tested Technology into that new world too, so this is probably an appropriate time to admit that my “720 is plenty” was missing a couple of caveats.

We’ll find room to touch on that in what follows…

THIS IS THE THIRD OPTOMA PROJECTOR Tested Technology has reviewed but its first-ever 4K projector. I must confess that together with the Philips monitor planned for review in the near further, it has changed my views on 4K.

The standard projector in most use here, a Viewsonic with 1080P resolution, has stood us in good stead for the past four years. In swapping over temporarily to the Optoma UHD51 the most obvious difference is that it’s around twice the size and weight.

It’s not the heaviest projector that’s ever crossed my desk—that was Epson’s EH-TW9200, which weighed in at just under 8.5Kg. The UHD51 is 5.22Kg, heavy enough to feel like a solid proposition, light enough to move around easily.

Other differences soon showed up. The main multimedia feed we use in the Tested Technology office is from the nVidia Shield TV, and happily this is able to handle 4K. No so, it turned out, the bidirectional 2-way HDMI switch we were using to send output either to the projector or to the 4K Philips monitor mentioned above.

Yes, Chinese imports can be surprisingly cheap, triggering the old “If it seems too good to be true…” knee-jerk. But the constant surprise for me these days is how good they actually can be.

In the event, the switch turned out to be wholly fit for purpose. But another culprit that had to be replaced was one of the cables, which, although it claimed to be “High Speed”, appeared to be causing blanking from time to time.

We’ll probably revert to this question of cables and peripherals in the upcoming review of the 4K Philips monitor. Because the lesson to be learnt here is that shifting 4K signals around demands sufficient bandwidth throughout the transmission system (including your Internet connection if you’re feeding in 4K from Amazon Prime or NetFlix).

It’s a Setup

Installing the projector was a breeze. I set it up as a direct replacement for the office ViewSonic, keeping it at a distance of about 300cm from the screen (well, white wall). Adjusting zoom and focus (with some help from the useful vertical +10% lens shift to move the display above the back of the office black leather sofa), this distance gave me a 250cm diagonal screen.

Unlike cheaper projectors, the zoom and focus wheels are geared together, so that altering the zoom retains the focus. A nice touch of class.

Using UHD51’s backlit remote control to switch on HDR SIM for a film that’s 80 years older than the projector (see below).

The small, slim backlit remote control is very similar to Amazon’s Fire TV Stick remote, but includes backlighting. It communicates with the projector through infra-red (IR) and so needs a theoretical direct line of sight. Theoretical, because, happily, the IR signal is strong enough to bounce and gave me complete control when pointed toward the screen.

Like Amazon’s remote, there’s a volume control for the feed to the projector’s two 5W speakers. The sound quality is, well, acceptable for built-in speakers—rather better than many others we’ve reviewed here because of the less cramped casing.

As the projector sits more or less beside me (quietly* blowing its hot air off to the right, so away from where I’m sitting) the built-in speakers aren’t best positioned. If fact, as I watch in the office on my own I much prefer to listen through a pair of good headphones.

Another reviewer has levelled accusations at the rotating colour wheel for being noisy, but our review sample showed no evidence of this.

Why is this desirable? In the setup I’m describing it’s an extra hassle, because I have to remember to mute the speaker volume if I just want the headphone output. Well, perhaps not that much of a hassle, as the UHD51 retains the setting after powering down. The payoff is in a family scenario where an audio impaired member might want to be listening through headphones or via a Bluetooth device while the rest of the family get its sound through the speakers.

Making Connections

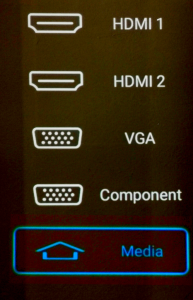

There are two HDMI inputs, which turns out to be useful for review test purposes, although in real life applications probably less so.

Really, Bidmead?

Well, yes—in a typical domestic setup the projector will probably be the output from an AV receiver, which would be able to do its own remote-controlled input switching. I’ve had a dual-HDMI projector connected to the Yamaha RX-V679 for several years now, with HDMI 2 left unused.

The double HDMI input does make sense if you’re not going to spend money on an AVR receiver and are happy to rely on the sound from the projector’s dual 5W speakers (well…) or (better) are feeding the output from the 3.5mm audio jack into a decent pair of headphones or (better still) via the S/PDIF digital audio connector into a simple amplifier system.

In this scenario you could connect a Chromecast device to HDMI 1 and something like an Amazon Fire Stick 4K to HDMI 2. But I really can’t imagine that you’d want to watch gorgeous 4K (or even 720p) movies for very long without a sound system to match.

If you’re going for the option to attach a device like the Amazon Fire TV stick directly to the projector, the USB power output you’ll see towards the right of the picture above will come in handy.

But don’t get excited about the RJ-45 Ethernet connector. The manual lists it as “a source”. But it won’t fetch YouTube from the Internet or be a conduit for movies and photos stored on your NAS. It’s there for what the manual calls “Web control”.

Web control allows your local area network to handle the duties of the manual remote control, turning the projector on and off, choosing the display mode and so forth. It’s a standard requirement for expensive permanent home cinema installations, a market for which the UHD51 qualifies as an entry level component.

You’ll notice that VGA output is also provided. You can get 1080p from a VGA connector (although I’m not sure why you would want to) but it certainly won’t give you 4K and/or HDR.

Phantom of the Media

Which brings us, sadly, to an instance of nonsense in the firmware design that I just can’t overlook. The proud UHD51 owner will get over it in time—the human spirit can endure much worse—but its sheer stupidity bothers the hell out of me.

The UHD51 is a cheaper version of the more capable UHD51A, which adds a bunch of features you might honourably conclude you just don’t need.

Among these is the ability to display various still photo and moving picture images directly from an attached USB stick*. The UHD51A has a menu option that allows you to select this USB input as “Media”.

Why do I mention this feature of the UHD51A that isn’t present in the UHD51? Because, although there is no Media function in the UHD51… the Media input option is still present in the menu. Its button takes up space at the bottom of the UI… but does nothing.

And when you start up the projector for the first time, Media is the input option it defaults to!

From the Optoma UHD51 Manual

4K and HDR

Having a 4K display system doesn’t mean you necessarily need 4K content. This is something we’ll be exploring further in the upcoming review of the Philips 328P6VUBREB 32″ 4K monitor. These devices do impressive upscaling (which means locally inventing 75% of the pixels!)

But to appreciate the full majesty of 4K you need a 4K source. You can get this from an appropriate Blu-Ray player, with prices for the 4K variety starting at around £150.

There’s a lot to be said for, and about, 4K. But I’ve split that off to a separate piece, “Too Much Reality?” where I also touch on the vexed question of 3D.

HDR (high dynamic range) is a different matter and arguably (well, I’d argue) a more valuable proposition than 4K. Two factors play into how we see the tones and colours of a projected picture: luma and chroma. HDR relates only to luma, the range of darkness to brightness the display can deliver.

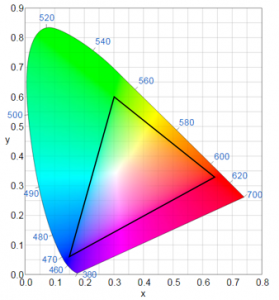

HDR effectively gives you whiter white and blacker blacks, but it’s not very meaningful to discuss this outside the context of chroma, the extent to which the display is able to reproduce the gamut of the 7 to 10 million different colours distinguishable by the normal human eye.

The tilted parabola represents the range of the millions of colours the human eye can distinguish. The black triangle shows the limits of Rec.709. It would be a mistake to read too much into this: the key takeaway is that while Rec.709 does a decent job with the blue and red extremes, it’s very weak on green.

The UHD51 meets a standard called “the Independent Telecommunication Union’s Recommendation BT.709” or just “Rec.709” for short. Optoma’s sales literature describes this as:

“…the international HDTV standard to guarantee accurate reproduction of cinematic colour exactly as the director intended.”

This strikes me as a bit of a stretch. Most of the world’s movies were made before Rec.709 was ever heard of, but let’s assume Optoma is talking about films made since 1990. Even so, the standard relates to HD television, not movie making. It embraces both luma and chroma and is essentially a specification about the best way of compressing “cinematic colour exactly as the director intended” into the rather smaller colour gamut that 1990’s HD TVs were able to provide. And, importantly, it includes nothing about HDR.

(Rec.709 flag-waving isn’t unique to Optoma among display manufacturers. But it’s important to understand what it is (a standard accommodating the limitations of television sets nearly two decades ago) and what it isn’t (a badge of honour for today’s displays).

For practical purposes, the UHD51 will reproduce movie luma and chroma not perhaps “exactly as the director intended” but almost certainly better than anything you’ve seen in your home. Thanks to the RGBRGB* colour wheel, the colours are impressive and in practice probably exceed the old early ’90s Rec.709.

It’s likely that Optoma’s marketing department decided that “meets Rec.709” sounded better than “almost reaches 75% of Rec.2020”.

And there’s always the added bonus that with the projector’s very extensive manual colour controls you can tune the picture precisely to your own taste.(Directors take great pride in colour grading. But once a movie has become a commodity and that control has passed to distributors and manufacturers the art risks getting munged. A domestic fix is democracy in action!)

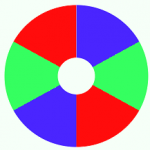

*An RGBRGB colour wheel comprises six sectors, each with a colour filter representing the three (additive) primary colours: Red, Green and Blue. The colour sequence is doubled so that the colour switching takes place at twice the physical speed of the wheel. Rapid colour switching is important as the technology depends on human persistence of vision.

*An RGBRGB colour wheel comprises six sectors, each with a colour filter representing the three (additive) primary colours: Red, Green and Blue. The colour sequence is doubled so that the colour switching takes place at twice the physical speed of the wheel. Rapid colour switching is important as the technology depends on human persistence of vision.

Projectors can improve the brightness of the picture by including a plain white segment and/or by using secondary colour filters: Cyan, Yellow and Magenta. These more translucent wheels will give brighter light from the same power lamp (useful for business presentations in daylight or smaller projectors less able to disperse heat) but at the cost of colour saturation. RGBRGB wheels typically give richer, truer colour rendition.

Faking It

HDR isn’t something the projector adds to the picture; the information about how to expand the luma has to be supplied by the source. Yes, the Optoma UHD51 does have a mode that allows you to fake HDR if the incoming signal doesn’t include it. This is HDR SIM (simulated HDR).

From the UHD51 Manual

HDR SIM.: Enhances non-HDR content with simulated High Dynamic Range (HDR). Choose this mode to enhance gamma, contrast, and color saturation for non-HDR content (720p and 1080p).

But I could only find one really good use for this when I was watching a pretty dreadful copy of an old black and white Cary Grant movie from the nineteen-thirties called *“The Amazing Quest of Ernest Bliss”.

Purists may howl but I found the movie much more watchable when I punched up HDR SIM from Image Settings/Display Mode on the projector menu.

Other image control features includes digital zoom, scaled as -5 to +25. Negative zoom might be useful to accommodate the image to the screen in a smaller room, although this kind of messing with the picture is deprecated by home cinema aficionados.

Another often deprecated feature I’m glad to find in this projector is what Optoma calls “PureMotion”. If a projector is capable of upscaling 1080p to 4K—in effect, locally synthesising 75% of the displayed pixels—it should also be able to increase the frame rate by inventing whole new frames to interpolate between the frames streaming in from the source.

Why would you want to synthesise interpolated frames? Traditional cinema has done something along these lines for decades, minimising the flicker of 24fps and improving the appearance of motion by showing the same frame twice or more by using a fast-moving rotating shutter.

Optoma’s Pure Motion (the same technique is used by other manufacturers under different names) is an electronically enhanced logical extension of the rotating shutter. You can find out why Tom Cruise doesn’t like it here.

The die-hard enthusiasts, however, will be pleased that this projector doesn’t offer the abominated “keystone” control, which in many entry-level home projectors allows you digitally to adjust the image shape to correct for any trapezium effect caused by the source and the screen not being in strict perpendicular alignment. I must confess I’ve always found this feature very useful, allowing me to install the projector where it suits me rather than the strict dictates of geometry.

You Are Entering the Third Dimension

3D is still with us and if you want it, the UHD51 has got it.

3D is still with us and if you want it, the UHD51 has got it.

I hadn’t watched a 3D movie for at least a couple of years before the UHD51 arrived for review this summer. The permanently installed projectors here are capable of handling it, but my feeling was that 3D was something I’d seen enough of and long ago shot my bolt writing about.

I was looking forward to the prospect of the UHD51’s higher resolution being put at the service of 3D. With some exceptions, 3D tends to be delivered in the same format as 1080p, with each individual frame split, vertically or horizontally, into two frames representing the left and the right views. Each sub-frame will be squashed down or squeezed sideways, but 3D logic in the display device restores it to the right shape. This means you’re actually getting half the resolution of HD per eye.

The technology essentially costs only pennies, comprising a pair of LED shutter lenses that open and shut alternately and an optical sensor that keeps this in sync with the left and right frames being shown sequentially on the screen.

The sync is achieved cheaply and reliably without the use of an additional wireless channel by the elegantly simple method of inserting a bright flash on the screen between each frame (which the viewer won’t see because both lenses will be shut at the time). The optical sensor reads the flash and triggers the shutters. These minimal electronics are powered by a small button battery, either rechargeable or replaceable.

To enjoy 3D, the UHD51 manual suggests that you should “Make sure a Blu-ray 3D player is installed”. We didn’t have one to hand but Tested Technology’s friend and colleague Barry Fox came to the rescue once again with the loan of a player he’d unearthed from his well-stocked attic of historic technology.

Barry’s Panasonic DMP-BDT210 was What HiFi’s Blu-ray Blu-ray player Product of the Year back in 2011, when the 3D fad was dying down. Barry and I watched some brief scenes from Avatar (2009), being reminded of the considerable dimming of the image that results from the need for 3D glasses. But the UHD51’s display (on a plain white wall) was still bright enough to be enjoyable.

Kodi has a 3D mode, so that menus and controls show up on their own separate plane when you’re wearing the glasses and have flipped the projector into 3D. The 3D formats you’ll encounter in a NAS feed are likely to be limited to side-by-side or over-and-under but this complicates setting up 3D when you’re pulling in the source over the LAN. You need to ensure that the movie, Kodi and the projector are all in the same 3D format, otherwise the screen becomes a blur of unnavigable control and menus, with or without glasses.

Mastering this requires some patience. For the average punter, the 3D Blu-ray player has a distinct advantage, simplifying the process with automatic switching.

There’s No Place Like Home (for 3D)

My opinion piece, “Too much reality?” sets out some of the serious fundamental shortcomings of 3D. It was an interesting discovery, though, that these are significantly ameliorated when you’re watching in the home. The convergence/focus problem is still there, of course, but in the home you can take breaks from viewing whenever you need*.

But in my book, it’s your house, your projector, your movie and your tea.

So?

I’m still of a view that 1080p (and even 720p) is as much resolution as you’ll need to enjoy a good movie. And I’m not sure that a bad movie is much improved by pumping up the pixel count. But there’s no arguing with the fact that 4K brings us nearer to the effectively infinite resolution of classic celluloid cinema.

It’s just that (for me, at least) screen resolution comes some way below script, cinematography, performance and pace—and even sound quality—in the list of factors that make a movie worth watching. Live performances like sport will of course benefit from the enhanced detail of 4K.

But…

You could buy a couple of 3D-capable 1080p projectors for the price of around £1300 that, for example, Richer Sounds is asking for the UHD51. Or a single projector with enough left over for a pretty good sound system. The 1080p projector will be lighter, smaller and perhaps a bit noiser but ready to give you several years of perfectly satisfactory home movies.

You might argue (I would) that the best thing about 4K is that it puts 1080p display devices in the sweet spot. Optoma’s HD27e, for example, comes with the same 6-year guarantee as the UHD51 for just £529.

However, sport may be your thing. Perhaps you’re looking to trump your neighbour’s 4K 60″ TV or are someone who must have the latest and greatest. Or do you want to show off your still photography in the best possible light?

If so, you have Tested Technology’s blessing to put you money on the UHD51. It’s solid technology from a creditable projector company with a deservedly huge share of the world market.

And 4K—despite my niggles—is without question the future. (Unless you’re happy to wait until 8K puts 4K in the sweet spot!)

Chris Bidmead

Optoma UHD51 Specifications

| Display technology | DLP (4K with pixel shifting) |

| Colour Wheel | RGBRGB |

| Resolution | UHD (3840x2160) |

| Brightness | 2,400 lumens |

| Contrast ratio | 500,000:1 |

| Native aspect ratio | 16:9 |

| Aspect ratio - compatible | 4:3 |

| Horizontal scan rate | 31 ~135Khz |

| Vertical scan rate | 24~120Hz |

| Light source type | Hot Lamp, 240W |

| Lamp life (hours) | 4000 (Bright), 15000 (Dynamic), 10000 (Eco) |

| Throw ratio | 1.21:1 - 1.59:1 |

| Projection distance (m) | 1.2m - 8.1m |

| Zoom | 1.3 (Manual) |

| Focal length (mm) | 12.81~16.74 |

| Lens shift | Vertical +10% |

| Inputs | 2 x HDMI 2.0, 1 x VGA (YPbPr/RGB), 1 x Audio 3.5mm |

| Outputs | Outputs 1 x Audio 3.5mm, 1 S/PDIF, 1 x USB-A power 1.5A |

| Controls | 1 x USB-A service, 1 x RS232, 1 x RJ45, 1 x 12V trigger |

| Noise level (typical) | 25dB |

| PC compatibility | UHD, WQHD, WUXGA, FHD, UXGA, SXGA, WXGA, HD, XGA, SVGA, VGA, Mac |

| 2D compatibility | 480i/p, 576i/p, 720p(50/60Hz), 1080i(50/60Hz), |

| 3D compatibility | Side-by-Side:1080i50 / 60, 720p50 / 60 Frame-pack: 1080p24, 720p50 / 60 Over-Under: 1080p24, 720p50 / 60 |

| 3D | Full 3D |

| Security | Security bar, Kensington Lock, Password protected interface |

| OSD / display languages | 10 languages: English, French,German,ltalian,Japanese,Portuguese, Russian, Chinese (simplified),Spanish |

| Operating conditions | 50C -. 400C, Humidity 85%, Max. Altitude 3000m |

| Remote control | Backlit home remote |

| Speaker | x2, 5W each |

| Extras Included: | Lens cap, AC power cord, Remote control with CR2025 battery, Basic User Manual |

| Power supply | 100/240V, 50/60Hz |

| Power consumption (standby) | 0.5W |

| Power consumption (min) | 249W |

| Power consumption (max) | 305W |

| Net weight | 5.22kg |

| Dimensions (WxDxH) | 392 x 281 x 118mm |

Great review many thanks