The previous episode got us started on the Scene buttons before I allowed myself to be sidetracked into a lengthy discussion about Internet radio (because it sounds so damn good on the RX-V679). I mentioned that the Scene buttons tie together particular physical inputs with whatever DSP Program you care to attach to them, so it’s probably time now to explain what DSP Programs are.

The previous episode got us started on the Scene buttons before I allowed myself to be sidetracked into a lengthy discussion about Internet radio (because it sounds so damn good on the RX-V679). I mentioned that the Scene buttons tie together particular physical inputs with whatever DSP Program you care to attach to them, so it’s probably time now to explain what DSP Programs are.

The DSP Programs

MUCH OF THE TIME WHAT pours into my music system is good old fashioned 2-track stereo, or even mono. I’ve already mentioned the DSP Program called “Straight”, which feeds the left and right front speakers and only uses DSP to corral the lower frequencies into the sub-woofer. Of course, as the name implies, if Straight should happen to receive a signal encoded as Dolby 5.1 audio it will distribute the extracted channels across all the speakers as expected.

“Straight” lets me hear the sound as the recording engineer intended. But the audio boffin behind, say, the 1956 LP “Songs for Swingin’ Lovers!”, wasn’t to know that I have a 5.1 surround sound system, and this Straight rendering, distributing the mono signal evenly between my two front speakers, leaves the centre and two rear speakers unemployed.

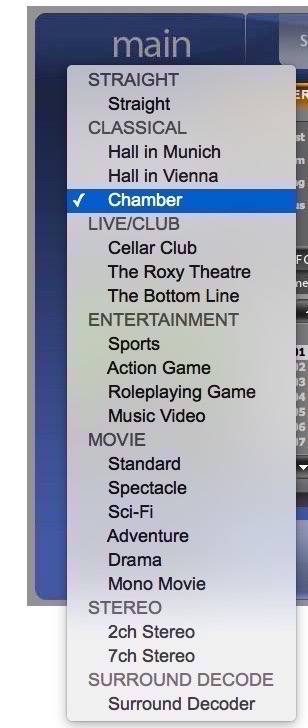

Thanks to those extra speakers the built-in DSP sound massager can change in myriad ways how the output bounces round the room and hits my ears. In an attempt to discipline the possibilities Yamaha has provided a number of handy presets, most of which can be user-modified to taste. Yamaha calls these presets “DSP Programs”.

The receiver comes with a set of 16 preset DSP Programs, arranged in groups. The “Classical” group comprises three different sized concert halls, using acoustic data gathered from real bricks-and-mortar venues.

In addition, as well as the “Straight” option there are DSP Programs for 2 channel and 7 channel stereo. The 2 channel stereo setting will use the DSP to present any incoming signal as stereo, however many channels the source has. Acting as a sort of “super-stereo” mode, 7 channel stereo puts the stereo signal into all your active pairs of speakers, front, back and surround, also adding mixed mono feed into the centre speaker. This is the (useful) default mode for the Radio scene, but can also enliven some regular stereo music sources (or make them sound horrible – be careful).

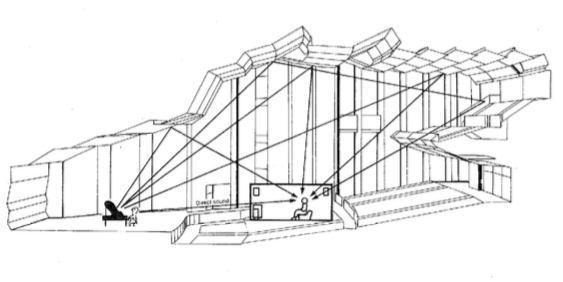

Diagram from the original DSP-1 manual showing how the acoustics of a concert hall can be reproduced in a small listening room.

There’s one more available setting in the On-Screen menu: Surround Decode. I’ve been using the word “surround” a lot here, but in this context it refers specifically to two now rather long in the tooth proprietary technologies from rival audio companies DTS and Dolby designed to extract convincing multi-channel sounds from stereo input.

The Yamaha RX-V679 offers two DTS variants: Neo 6:Cinema and Neo:6 Music . There are a total of six Dolby Surround Decode modes: one each of Music, Movie and Games for Dolby ProLogic II and the more recent Dolby ProLogic IIx, which synthesises an additional pair of back surround channels for 7.1 surround systems. Dolby ProLogic II gets even cleverer if the original stereo signal has been specially encoded for the system, when it’s able to provide output that approximates to discrete 5.1 channels.

Hot debate rages in audiophile circles about which of these is better, or indeed whether they should exist at all. Only your own ears can tell you that, but personally I’m very glad they’re there as part of the very useful RX-V679 toolbox for bringing music and movies to life.

Hot debate rages in audiophile circles about which of these is better, or indeed whether they should exist at all. Only your own ears can tell you that, but personally I’m very glad they’re there as part of the very useful RX-V679 toolbox for bringing music and movies to life.

You might be wondering what the option, available only on the remote control and the front panel, marked “Pure Direct” does. This has evidently been provided by Yamaha to placate a dyed-in-the-wool old-school audio enthusiast friend of mine, who I shall refer to here only as “Barry”. This switch deactivates DSP altogether, eliminates any subwoofers attached, and effectively turns the RX-V677 into a straightforward hi-fi amplifier. It even blanks the LED display on the front panel.

You might be wondering what the option, available only on the remote control and the front panel, marked “Pure Direct” does. This has evidently been provided by Yamaha to placate a dyed-in-the-wool old-school audio enthusiast friend of mine, who I shall refer to here only as “Barry”. This switch deactivates DSP altogether, eliminates any subwoofers attached, and effectively turns the RX-V677 into a straightforward hi-fi amplifier. It even blanks the LED display on the front panel.

I tapped Barry for his views on DSP magic, but he more or less refused to discuss the question. His argument put the control firmly in the hands of that engineer responsible for capturing the original sound. What’s on the recording — music, acoustics and all — is what the engineer judged you should be listening to at home. A DSP system that fiddles with the frequencies, delays and wave-phases to add fake acoustics might be ok as a way of enhancing an action movie soundtrack. But for pure music it’s anathema. End of.

OK. Because it cuts out the sub-woofer, the “Pure Direct” setting will make sense if (and only if) your two front speakers are capable of handling the full frequency response from, say, 20 to 20,000 Hz. This doesn’t apply to my own (and most people’s) surround sound system, which depends on the subwoofer to reproduce the lower frequencies. Even so, you are probably not going to want to throw away the advantages of DSP, because — in my view — Barry’s argument overlooks some important points.

The first, brought to my attention by another audiophile chum I shall call “Rupert”, is that if digital signal processing had been available in the early days of hi-fi, it would have been the technology of choice. All analogue processing inevitably involves some kind of compromise, and will introduce its own quirks and colouring. Even if you see the task as recreating the original exactly as the sound engineer heard it, it turns out that analogue isn’t the best way of doing this, and it simply can’t touch digital when it comes to complete transparency. If you want to record a sound signal, transfer and/or transmit it, amplify it and eventually reproduce it as faithfully as possible, the more digital linkage you have in the chain the better.

In fact this is what some of the most expensive audiophile systems do. Midrange systems like the RX-V679 (and until recently all the others) work their digital magic in the pre-amplifier stage only. Beyond that, DACs (digital to analogue converters) turn the signal into the old-fashioned analogue waveforms that conventional power amplifiers expect. There are two reasons for this: digital components at pre-amp power levels are relatively cheap; and analogue power amplifier circuitry has over a century of experience behind it.

But instead of incorporating DACs into the preamplifier and carrying out the rest of the amplification in the analogue domain, amplifiers like the Italian-built Wadia Intuition keep the signal digital all through the power amplifier stage, using (expensive) power DACs right at the end of the chain before presenting it to the loudspeakers. However, one good reason to stick with the RX-V679 is that a Wadia Intuition will cost you around ten times the price.

The second point I made to Barry is that there will always more than one set of acoustics between what the sound engineer is recording and the air turbulence arriving at your ears in your living room. The recording venue adds its own colouration, but so does the room the recording is being played back in. Which means the engineer can have no real idea of how the output’s going to sound to you.

In my experience, having DSP capability on hand in the home also turns out to be a bonus for many classical music recordings. One example might be Glenn Gould’s famous mid-50s recording of the Goldberg Variations. Studio piano recordings tend to be closely miked, but in concert performances the sound will be enriched by the acoustics of the hall. Indeed, modern grand pianos are specifically built for concert performance, so if the close miking in the studio is relying on your living room acoustics to fill out the resonance it will probably fall well short of how the piano was designed to sound.

In my experience, having DSP capability on hand in the home also turns out to be a bonus for many classical music recordings. One example might be Glenn Gould’s famous mid-50s recording of the Goldberg Variations. Studio piano recordings tend to be closely miked, but in concert performances the sound will be enriched by the acoustics of the hall. Indeed, modern grand pianos are specifically built for concert performance, so if the close miking in the studio is relying on your living room acoustics to fill out the resonance it will probably fall well short of how the piano was designed to sound.

Recording Glenn Gould’s Goldberg variations in the 1955 studio presented a very special problem. After soaking his arms up to the elbows in near-boiling water for 25 minutes prior to performance, the twenty-two-year-old Gould felt compelled to hum along as he tickled the ivories, often in counterpoint, and not necessarily always in tune. He had always done this since childhood, and no amount of pleading from the studio engineer could shut him up. You can still hear Gould’s mutterings on the mono recording, although the mikes are placed particularly close to the strings to minimise this. Reproduced through the sort of “Pure Direct” path that Barry would advocate, Gould’s Steinway sounds unnaturally intimate.

It’s possible that this “crooning grand piano” sound may have been what Gould was aiming for, one of his many performance eccentricities. But why shouldn’t the listener have the option to open up the performance and place it in the concert hall, which is really where any full-blooded Steinway belongs? The Yamaha RX-V679’s wicked DSP-twiddling allows me to relocate Gould in stereo onto the stage of a “Hall in Munich”. And for what it’s worth I think the performance seems greatly improved.

Mostly I stick to “Straight”, although I must also confess, for example, to layering DSP acoustics over the magnificent but rather dry 1939 Casals Bach Cello mono recordings. The “7ch Stereo” DSP Program adds a light touch of bathroom that helps bring the playing marvellously to life. Am I evil?

In the first episode of this Yamaha RX-V679 review/adventure I touched on the merits of trashing your headphones and going back to old-fashioned loudspeaker listening. The counter-argument young Steve was making was chiefly economic: a decent pair of headphones will cost you around £200; to kit out your living room with speakers and a hi-fi unit would be a lot more.

In the first episode of this Yamaha RX-V679 review/adventure I touched on the merits of trashing your headphones and going back to old-fashioned loudspeaker listening. The counter-argument young Steve was making was chiefly economic: a decent pair of headphones will cost you around £200; to kit out your living room with speakers and a hi-fi unit would be a lot more.

But those £200 headphones won’t be much use on their own. Yes, these days you mostly drive them from your smartphone, which is a sunk cost, and you’re using the phone for other things as well. So headphone listening does look a lot cheaper at first glance.

The surprising fact is that the capital cost of the kit in both cases can pan out around the same.

You can pick up a very acceptable 5.1 speaker system with an active subwoofer for around the same price as the headphones. And if you’ve ever thought of buying your smartphone outright instead of on a 2 year contract (something many money-conscious users are discovering is worth doing) you’ll know that the latest top end handsets work out at around £600, which happens to be the RRP of the RX-V679.

Yes, there are cheaper phones. But there are also cheaper AV receivers. Yamaha’s previous equivalent model, the RX-V677, is going for around £220 if you shop around, and there are perfectly decent AV units available for a lot less than that. My point is that price shouldn’t be the deciding factor here. The key question is whether you just want to wear your music for comfort and protection, or whether you want actually to LISTEN to it. The RX-V679 has had me revisiting my music collection with new ears, and it’s been a revelation.

Yes, there are cheaper phones. But there are also cheaper AV receivers. Yamaha’s previous equivalent model, the RX-V677, is going for around £220 if you shop around, and there are perfectly decent AV units available for a lot less than that. My point is that price shouldn’t be the deciding factor here. The key question is whether you just want to wear your music for comfort and protection, or whether you want actually to LISTEN to it. The RX-V679 has had me revisiting my music collection with new ears, and it’s been a revelation.

One last point, while we’re on the subject. If those £200 headphones happen to carry a prized logo you might want to know how much you’re paying for the technology and how much for the much-vaunted trademark. An engineer at the investment fund Bolt, which specialises in IT startup companies, did a tear down of a pair of £200 Beats headphones. Total cost of the plastic, metal and electronic components was around 11 quid. The metal parts, by the way, had no acoustic or electronic function. They were just there to add a bit of authentic heft.