The big question arising here, I suppose, is: does qualification as a “flagship” smartphone mandate a first-class camera array? Or is good-enough good enough?

As I hinted in part 1, there’s not a lot of point spending extra money on a wizard camera array that you won’t be competent to deploy. If it’s ok at its day job and perhaps rather less competent in low light but night shots aren’t in your repertoire anyway, nothing is lost. And that seems to be the case with this RedMi Note 10 Pro.

The Camera Array

That camera bump is probably the very first thing you notice about the phone. It’s ugly. The bundled “plastic mac” case goes some way to protect it with an obtruding rim but this only serves to emphasise the “feature”.

This is a bump that is not in the least apologetic about its presence. The words “Ultra Premium” that form part of the array seem to be a defiant boast (and have been misread as such in reviews). In fact, they’re there to identify two of the cameras that make up the array: the Ultra-wide lower camera and the Premium 108mpx camera at the top.

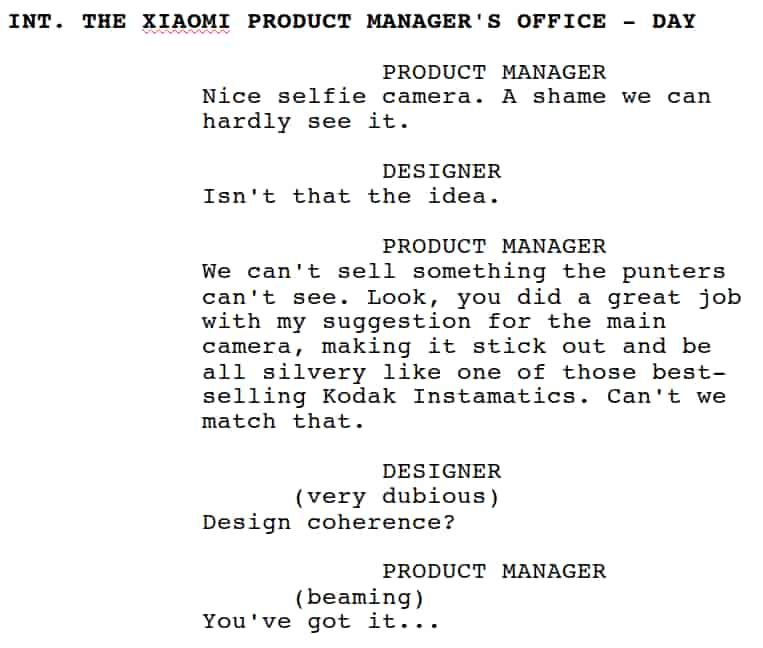

Doubly unfortunate is the way that the design reminds us—at least, those of my generation—of a less than lovely range of cheap cameras launched in the early ’60s. The sunburst chrome frame around the Premium camera seems to shout “Kodak Instamatic” and all through the weeks of putting this review together I haven’t been able to get this out of my mind.

Doubly unfortunate is the way that the design reminds us—at least, those of my generation—of a less than lovely range of cheap cameras launched in the early ’60s. The sunburst chrome frame around the Premium camera seems to shout “Kodak Instamatic” and all through the weeks of putting this review together I haven’t been able to get this out of my mind.

I was relieved to discover a protective case on eBay that manages completely to cover the whole camera bump, leaving only holes for the individual cameras. The bump is still there, but only you will know of the Kodak Instamatic lurking below.

I’ve gone on too long about the aesthetics of this camera array. Time to get down to what it does, and how.

The Different Cameras

Many of the smartphone reviews you’ll re ad on the Web refer to the “rear camera” and the “front camera”. This has always confused me. As a once-upon-a-time wet-negative portrait photographer, for me the camera back was where the viewfinder was and the camera front was the business end pointing at the punter. So for me, the small camera watching you through a hole in the viewfinder has always been “the back camera”.

ad on the Web refer to the “rear camera” and the “front camera”. This has always confused me. As a once-upon-a-time wet-negative portrait photographer, for me the camera back was where the viewfinder was and the camera front was the business end pointing at the punter. So for me, the small camera watching you through a hole in the viewfinder has always been “the back camera”.

Which is why you’ll see me referring to the “main camera” and the “selfie camera”.

That’s just historic confusion on my part. But there’s a current confusion floating around the Web that is really misleading. These days, that “main camera” is a “camera array”—a bunch of small, independent cameras capable of working in concert under the supervision of software.

It isn’t—as many reviewers often tend to report—a single camera with a bunch of different lenses.

At the launch, the Redmi Note 10 Pro main camera array was described as “boundary challenging”. In some respects, this is no exaggeration, although Xiaomi’s use of the term fifty-nine times (I counted) during the launch presentation to describe several different aspects of the Redmi Note 10 series did tend to dilute its meaning.

There are four separate elements to the rear camera array:

- The Premium Camera: 108MPx (0.7µm pixels and f/1.9)

- The Macro camera, 5Mpx (telemacro f/2.4. Autofocus between 3cm and 10cm)

- The Depth sensor: 2MPx (“time-of-flight” camera)

- The Ultrawide camera: 8MPx (fixed focus)

The Premium Camera One hundred and eight is a lot of pixels and when you cram that many into a sensor array designed for a small handheld device the individual pixels need to be rather small. Smaller pixels gather fewer photons and the less light each pixel gets the more guesswork is involved in assessing the picture. You get technically higher resolution but a “noisier” picture—visual “noise” being defined in this context as random data that fuzzes up the signal data you’re aiming to capture.

Earlier this century, the pixel count inside a camera array was usually taken to be a direct measure of the overall quality of the camera. When 5Mpx cameras became the standard there was no question that they were better in every way than the original sub-Mpx cameras.

But when higher pixel counts began to shrink the size of each individual sensor it became clear that ever higher resolutions didn’t necessarily mean better pictures.

So what are we to make of a 108Mpx camera? Yes, its pixels are small but that turns out not to be an issue when photographing a well-lit scene. With each pixel satiated you end up with a very high resolution photograph. Night photography poses a problem. But there’s an ingenious solution: pixel binning. Bundle the information collected by a bunch of adjacent pixels and tell the system it all came from a single pixel. Effectively, you’re now working with much larger pixels.

Obviously, this will give you a lower resolution picture. But with 108 Mpx you’ve got plenty of resolution to spare. This camera operates by default by binning nine adjacent pixels into one. 108 divided by 9 is 12. And a 12Mpx camera is a resolution about 40% better than 4K.

This camera lacks the cunning optical zoom now used in several of the flagship cameras. But from the abundance of pixels you might think it capable of zooming digitally well beyond its actual limit of 10X. The reason for this limit is probably the lack of optical image stabilisation, (OIS) a missing feature that (in our view) relegates this smartphone from the flagship league. Without OIS, even at 10x you’ll need a very steady hand (or a lot of light and a fast shutter setting) to get a crisp picture.

The Macro Camera is equipped with a “telemacro” lens. Macro means “big” and “tele” means “distant”. So what the word is trying to convey is that you can take what are generally called “closeups” without actually being, er, close up.

This is promoted as an important improvement on mere “macro” lenses or combined macro and ultrawide lenses which require the camera to be in very close proximity to the subject, often causing shadowing problems. The Oppo Reno 2 has a perfectly decent macro function as part of its ultra-wide camera. But that requires the phone to be about 2″ away from the subject. The dedicated Redmi Note 10 Pro telemacro camera takes the equivalent shot from twice the distance, leaving ultra-wide photography to a separate camera.

The Depth Sensor is a only camera in the sense that it captures photons and has logic that processes their input. But it doesn’t produce a picture. It’s actually measuring the distance to the subject by timing how long it takes for a light beam to bounce off it. A two megapixel array is a much as this needs. The infrared light used to make this measurement is emitted from the tiny red LED just visible below the main flash LED.

The Ultrawide camera has its focus fixed at infinity and will capture everything within a 118° angle. With a very wide range of vision like this, the depth of field is huge and you can expect everything beyond about 40cms to be sharp. Great for landscape shots.

The widest Ultrawide format. You’ll notice the watermark in the bottom left corner. It’s an option that you can tailor with your own text and—unusually—subsequently remove in the Xiaomi Gallery app if you choose

Despite the lack of OIS, this camera array is capable of some remarkable feats of photography, all pulled together by a very well-designed Xiaomi Camera App. I don’t include in this the various gimmick features like selfie beautifying (what need have I of that, the reader may well ask), and something called Vlog mode, which—unless I’m missing something—seems only able to create very short (mere seconds) movies with fragments of music plonked onto the audio track.

Philosophical discussion before breakfast. The effect isn’t perfect—the old gentleman on the right is missing one of his feet.

Among the gimmicks is Xiaomi’s Clone mode, which does a remarkably good job of faking your doppleganger (or even tripleganger, if that’s the right word). A more generally useful feature is Document Mode, which automatically crops text material and cleans it up for legibility.

The best part of the Camera app is the Pro mode. It saves stills in RAW, allows you to choose which of the three cameras to use and gives you full control over white balance, focus, shutter speed, ISO and exposure, with the option to leave the first three of these parameters on auto.

The camera array is good for movies too, of course, although the lack of OIS shows up rather badly when you’re shooting handheld in 4K at the maximum rate of 30 frames a second. If you take this down to 1080p (30fps or 60fps) a degree of electronic image stabilisation (EIS) kicks in which helps somewhat to keep things smooth. As a bonus, if you like this sort of thing, the Xiaomi Gallery’s movie editor function can download a small selection of electronic music to accompany your video. Or you can optionally add your own music using this editor.

Explore further and you’ll find downloadable video filters and even templates that automatically create montages from a selection of videos. Useful if you’re away from your computer (or short of time and want to pass yourself off as an artist). But no substitute for a real non-linear video editor on a computer.

The Selfie

There’s an oddness about this selfie camera, too. Xiaomi have minimised its intrusion on the screen by reducing it to close to pin-hole dimensions. This seems like a better engineering solution than the Oppo Reno 2’s mechanical “shark-fin” pop-up selfie camera, at least until through-the-screen cameras arrive.

But… They’ve made the extraordinarily odd design choice of framing the pin-hole with a reflective silver ring. Making it a stand-out screen feature.

Beware of the Bloatware

There’s one thing to get out of the way before we conclude our judgment (spoiler: it’s positive). This smartphone helps to keep its price down by employing bloatware. I understand that the company is somewhat notorious for this.

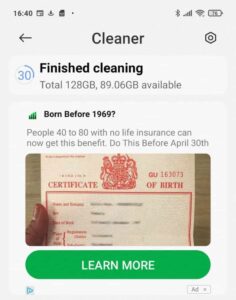

I didn’t so much mind finding Facebook and TikTok waiting for me preinstalled. No doubt Xiaomi will be getting paid to serve up apps like these a la carte but no sweat: both were easily removed in the usual way. But it took me a while to discover that an app innocuously named “Downloads” was not what you might think it to be. Another app, “Cleaner” will remove cache files unnecessarily clogging up your storage but not without nudging you into installing “BEST FREE GAMES” or selling you life insurance. The app also entices you in the direction of an “MIUI Feature Tutorial”, which sounds reasonable enough as well as being a useful crib for any reviewer of the phone. However, before you can get to the tutorial you’re encouraged to sign up to Facebook.

I didn’t so much mind finding Facebook and TikTok waiting for me preinstalled. No doubt Xiaomi will be getting paid to serve up apps like these a la carte but no sweat: both were easily removed in the usual way. But it took me a while to discover that an app innocuously named “Downloads” was not what you might think it to be. Another app, “Cleaner” will remove cache files unnecessarily clogging up your storage but not without nudging you into installing “BEST FREE GAMES” or selling you life insurance. The app also entices you in the direction of an “MIUI Feature Tutorial”, which sounds reasonable enough as well as being a useful crib for any reviewer of the phone. However, before you can get to the tutorial you’re encouraged to sign up to Facebook.

There was also a noisy barrow-boy aura surrounding the folders you use to herd apps on the desktop. Dropping one app on top of another is the standard Android method of folder creation. But the MIUI desktop riffs on this by offering to pop up a selection of “Promoted Apps” when you rename that folder from its default, “Folder” to something more appropriate.

This is when I explored Downloads and found that instead of being a download accelerator (like the Advanced Download Manager in the Google Play Store) or a way of organising your existing downloads, it was another gateway into a market selling “Recommended Product”. And collecting your user data. Worse, it was seemingly irremovable.

Every smartphone needs a file manager. The Redmi Note 10 Pro provides one as a part of the System Apps—which is to say it’s baked into the system and can’t be removed in the usual way. And this app too serves up advertisements.

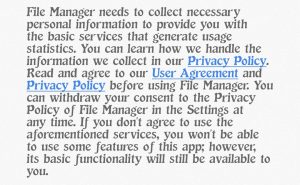

“Basic functionality” still available. You’ll also see here the effect of using the My Queen system font the phone collected on its visit to India.

The app warns that “File Manager needs to collect necessary personal information to provide you with the basic services that generate usage statistics.” So that the app can serve you targeted ads, evidently. It turns out that although you can’t remove the app (without some Android Debug Bridge adroitness, see below) you can opt out of the collection of personal information.

As a newbie to MIUI this rang alarm bells. You may feel differently about this, of course, but it’s Tested Technology’s mantra that tools like your smartphone and your notebook are there for you do to things with, not for things to be done to you.

Xiaomi’s evidently not unsympathetic to this view, however. Their privacy policy is fairly clearly set out and easy to access, although disingenuous in places. Instead of “What we want is to squeeze as much value for ourselves as we legally can from the fact that you’re using our device as your window on the world” the punter is lead to understand that “Ultimately, what we want is the best for all our users…”

This is all fairly standard stuff and Xiaomi aren’t being especially egregious here. Your personal data are gathered by the handful, certainly, then anonymised and mulched down according to legal requirements. But this is where I found that Xiaomi, to its credit, goes a little further in allowing you to shake free from all this bustling undercover commerce.

What that “Ultimately” clause amounts to is a reasonable, if perhaps under-announced, get-out for the user. A Web tip I came across lead me to a buried section in the Settings called “Authorisation and revocation”.

I couldn’t find this from the top menu but if you start to type “Author” into the search box you get a screen with a set of toggles that controls the bloatware features like Download. I allowed Download to live on now that I knew how to kill it but did revoke authorisation for msa (MIUI System Ads).

This made me feel a little better about Xiaomi. I know that some people don’t mind the bloatware or are able to put up with it and others feel it’s all part of the fun. Discerning Tested Technology readers are probably better off without it and it’s good to be able to report that it can be cleaned out without having to plumb the depths of ADB (the Android Debug Bridge, which is how the real techies do it).

It’s not all plain sailing, however. You’re warned that if you use these opt-outs the apps in question might become “virtually unusable”.

Winding Up

Despite the enthusiasm for this smartphone across the Internet (which Tested Technology shares) the Xiaomi Redmi Pro turns out to be a “not quite flagship” offering. The camera array is well-conceived and supported by an excellent camera app. Its physical design however is, to put it kindly, eccentric and the lack of optical image stabilisation helps relegate the phone to “not quite”.

The long-lasting, fast-charging 5000mAh battery together with the 30A charger bundled in is a huge asset, as is the 120Hz refresh AMOLED screen. This is all good stuff. But the bloatware factor that helps subsidise this can’t be ignored either. We’ve seen that it can be ameliorated, although, after a month exploring this phone, it’s not clear exactly what the disadvantageous side-effects of this will be.

There’s a possible radical solution to this that we can’t recommend, as we haven’t tested it. Back in the day, we reviewed several Wileyfox phones and commended them for their use of the Cyanogen open source variant of Android. Cyanogen, sadly, went up in a puff of rather acrid smoke at the end of 2016. Wileyfox reverted to its own version of Android but Cyanogen was quickly resurrected as a new project called LineageOS.

LineageOS has survived and thrives today. The good news is that it’s now unofficially available for the Redmi Note 10 Pro. It’s early days but there’s a decent chance that this will become official, stable and fully functional.

Better classified as an exemplary mid-range smartphone, the RedMi Note 10 Pro is available on Amazon UK for £170.

Chris Bidmead